News

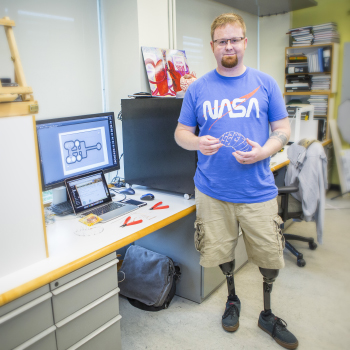

Brian Fountaine, an Army veteran and double-amputee, found inspiration working as an artist-in-residence in the lab of SEAS faculty member Kit Parker. (Photo by Eliza Grinnell/SEAS Communications.)

Brian Fountaine’s sketchpad is filled with detailed drawings of human organs and meticulous diagrams of scientific experiments. For the aspiring graphic designer, a rising senior at Northeastern University, the images are strikingly different from the illustrations he typically produces.

Fountaine put his creative eye to use as an artist-in-residence this summer in the lab of Kit Parker, Tarr Family Professor of Bioengineering and Applied Physics. He joined the lab as a participant in the Research Experiences for Undergraduates program, which enables college students to work on scientific projects in the labs of Harvard researchers.

For the 34-year-old, working in a research lab at the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences has been both surreal and unexpected.

Growing up in a tight-knit blue-collar family, Fountaine never planned on attending college. Immediately after graduating from high school, he enlisted in the Army, deploying to Iraq with the initial post-9/11 invasion in 2003. During his second deployment in 2006, tragedy struck. While on patrol near Baghdad, the Humvee he was commanding detonated a pressure plated improvised explosive device. The resulting blast blew off Fountaine’s lower legs.

Growing up in a tight-knit blue-collar family, Fountaine never planned on attending college. Immediately after graduating from high school, he enlisted in the Army, deploying to Iraq with the initial post-9/11 invasion in 2003. During his second deployment in 2006, tragedy struck. While on patrol near Baghdad, the Humvee he was commanding detonated a pressure plated improvised explosive device. The resulting blast blew off Fountaine’s lower legs.

“When I finally woke up, I was in Germany, on a ventilator and hooked up to all these machines,” he said. “I started the long process of learning to walk again, and learning how to live my life again.”

It wasn’t easy. Lacking any clear goals, Fountaine sunk into a deep depression. He had planned on making a career out of the military, but that dream had been shattered. Fountaine’s wife, Mary, finally convinced him to give college a chance.

“My whole idea of what college life was like came from movies like ‘Van Wilder’ and ‘Animal House.’ I thought it was a big joke,” he said.

Using the Army’s vocational benefits, he enrolled in Cape Cod Community College and quickly found that higher education appealed to him. He added more and more classes until he was full-time, graduating with as associate’s degree in graphic design. He transferred to Northeastern University to complete a bachelor’s degree.

“I gravitated toward graphic design because I’ve always been artistic. I was really good with my hands and enjoyed sculpting, drawing, and painting,” he said. “I really liked learning new things again.”

Fountaine started at Northeastern shortly after the Boston Marathon bombing, a devastating tragedy that struck especially close to home for the double-amputee. He began sneaking into the hospital and meeting with survivors who had lost limbs, sharing words of encouragement and advice.

“I felt this calling where I had to help out and do something,” he said. “I told them that it’s not the end of the world. You might have lost some limbs—your body might be different—but your heart and your spirit are still intact. You can still accomplish things in life that you’ve always wanted to do.”

As he developed close relationships with injured civilians, Fountaine learned about their struggles to afford prosthetic devices. Military benefits covered his medical expenses, but these individuals often had to make sacrifices to afford prosthetic devices.

Fountaine wanted to help, and saw 3D printing technology as a potential solution. Printing limbs from durable carbon fiber could be significantly faster and cheaper than current processes. He submitted a proposal to the Ford Motor Company’s College Community Challenge, and won $35,000 to purchase 3D printers and software for the project. His work caught the attention of the local press.

Parker, an Army combat veteran, read Fountaine’s story and was inspired by his dedication to help others. He reached out to Fountaine and invited him to join his lab group for the summer as part of the REU program.

“When they first contacted me, I didn’t know how to take it,” Fountaine recalled. “A research lab at Harvard University? This was a foreign idea to me. I had never thought about working in a science field before.”

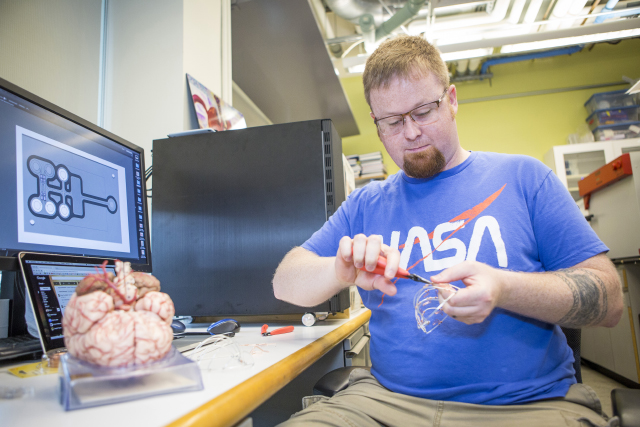

Fountaine spent the 10-week program working closely with researchers in the Parker lab, documenting experiments and drawing diagrams and figures for research papers. He created acrylic diagrams of organs, carefully colorized microscopic images, and enhanced computerized illustrations of organs on a chip.

That research, in particular, resonates with Fountaine. Organs on a chip could enable physicians to run drug screens through a microchip to see if they would be effective or have negative side effects on a specific patient. Another project that piqued his interest focuses on nanofibers to improve wound care.

“As an amputee, I went through a lot of wound care. And I’ve been on dozens of medications, some which didn’t work well and others that had really bad side effects,” he said. “It has been really interesting and inspiring to see people working on projects that will not only benefit me, but also my fellow brothers and sisters in arms who have been hurt and are trying to live normal lives again.”

That’s not to say that the work is always easy. Creating detailed figures for journal articles, for instance, requires one to stick to a strict set of design parameters. Fountaine, used to more artistic freedom, has had to tailor his personal style to the needs of the researchers and publications.

But he still squeezes in a bit of artistic flair wherever he can. As he’s learned more about science, he has seen striking parallels between the scientific world and the artistic one.

“If you look hard enough, there is a lot of beauty in science,” he said. “A molecular-level image of cells or fibers is full of different forms, colors, and tones.”

While Fountaine has enjoyed his time in the Parker lab, he is already looking to the future. With one year of college left, he is hoping to launch a nonprofit organization to develop 3D-printed prosthetics.

The experience in Parker’s lab opened his eyes to the power of science, and has helped him to understand some of the principles of engineering, lessons that will be critical as he works with mechanical engineers to develop effective and affordable 3D-printed prosthetics.

He hopes his story can inspire other injured veterans to pursue an education and take on large-scale challenges.

“After I got hurt, I had to decide if I was going to laugh about this or if I was going to cry about it,” he said. “I chose a long time ago that I was going to laugh about it. And it helps. Have a good sense of humor and find some purpose. Find that next objective and strive for it. Grab it and don’t let go.”

Working in the lab of Kit Parker has taught graphic designer Brian Fountaine that there is beauty in science. (Photo by Eliza Grinnell/SEAS Communications.)

Topics: K-12

Cutting-edge science delivered direct to your inbox.

Join the Harvard SEAS mailing list.

Scientist Profiles

Kit Parker

Tarr Family Professor of Bioengineering and Applied Physics

Press Contact

Adam Zewe | 617-496-5878 | azewe@seas.harvard.edu