News

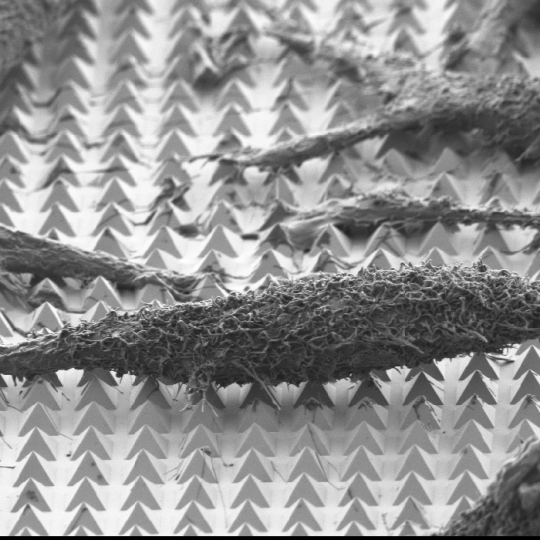

A scanning-electron microscope image of chemically-fixed HeLa cancer cells on the substrate. The tips of the pyramids create tiny holes in the cell membranes, allowing molecular cargo to diffuse into the cells. (Image courtesy of Nabiha Saklayen/Harvard SEAS)

The ability to deliver cargo like drugs or DNA into cells is essential for biological research and disease therapy but cell membranes are very good at defending their territory. Researchers have developed various methods to trick or force open the cell membrane but these methods are limited in the type of cargo they can deliver and aren’t particularly efficient.

Now, researchers from the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS) have developed a new method using gold microstructures to deliver a variety of molecules into cells with high efficiency and no lasting damage. The research is published in ACS Nano.

“Being able to effectively deliver large and diverse cargos directly into cells will transform biomedical research,” said Nabiha Saklayen, a PhD candidate in the Mazur Lab at SEAS and first author of the paper. “However, no current single delivery system can do all the things you need to do at once. Intracellular delivery systems need to be highly efficient, scalable, and cost effective while at the same time able to carry diverse cargo and deliver it to specific cells on a surface without damage. It’s a really big challenge.”

In previous research, Saklayen and her collaborators demonstrated that gold, pyramid-shaped microstructures are very good at focusing laser energy into electromagnetic hotspots. In this research, the team used a fabrication method called template stripping to make surfaces — about the size of a quarter — with 10 million of these tiny pyramids.

The beautiful thing about this fabrication process is how simple it is.

"The beautiful thing about this fabrication process is how simple it is,” said Marinna Madrid, coauthor of the paper and PhD candidate in the Mazur Lab. “Template-stripping allows you to reuse silicon templates indefinitely. It takes less than a minute to make each substrate, and each substrate comes out perfectly uniform. That doesn't happen very often in nanofabrication."

The team cultured HeLa cancer cells directly on top of the pyramids and surrounded the cells with a solution containing molecular cargo.

Using nanosecond laser pulses, the team heated the pyramids until the hotspots at the tips reached a temperature of about 300 degrees Celsius. This very localized heating — which did not affect the cells — caused bubbles to form right at the tip of each pyramid. These bubbles gently pushed their way into the cell membrane, opening brief pores in the cell and allowing the surrounding molecules to diffuse into the cell.

Nanosecond pulses of laser heat the gold-covered pyramids, causing bubbles to form right at the tip of each pyramid. These bubbles gently push their way into the cell membrane, opening brief pores and allowing molecules to diffuse in. Actual pyramids are uniform in height. (Video courtesy of Nabiha Saklayen/Harvard SEAS)

“We found that if we made these pores very quickly, the cells would heal themselves and we could keep them alive, healthy and dividing for many days,” Saklayen said.

Each HeLa cancer cell sat atop about 50 pyramids, meaning the researchers could make about 50 tiny pores in each cell. The team could control the size of the bubbles by controlling the laser parameters and could control which side of the cell to penetrate.

The molecules delivered into the cell were about the same size as clinically relevant cargos, including proteins and antibodies.

Next, the team plans on testing the methods on different cell types, including blood cells, stem cells and T cells. Clinically, this method could be used in ex vivo therapies, where unhealthy cells are taken out of the body, given cargo like drugs or DNA, and reintroduced into the body.

“This work is really exciting because there are so many different parameters we could optimize to allow this method to work across many different cell types and cargos,” said Saklayen. “It’s a very versatile platform.”

Harvard’s Office of Technology Development has filed patent applications and is considering commercialization opportunities.

“It’s great to see how the tools of physics can greatly advance other fields, especially when it may enable new therapies for previously difficult to treat diseases," said Eric Mazur, the Balkanski Professor of Physics and Applied Physics and senior author of the paper.

This research was supported by the National Science Foundation and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. It was coauthored by Marinus Huber, Marinna Madrid, Valeria Nuzzo, Daryl Inna Vulis, Weilu Shen, Jeffery Nelson, Arthur McClelland and Alexander Heisterkamp

Topics: Bioengineering

Cutting-edge science delivered direct to your inbox.

Join the Harvard SEAS mailing list.

Scientist Profiles

Eric Mazur

Balkanski Professor of Physics and Applied Physics

Press Contact

Leah Burrows | 617-496-1351 | lburrows@seas.harvard.edu