Key Takeaways

-

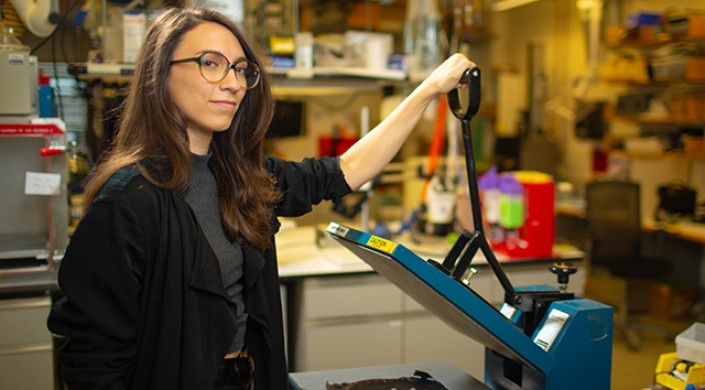

Graduate student Vanessa Sanchez blends fashion design and engineering to develop smart textiles and wearable robotics.

-

She has helped create textile-based actuators and sensors for soft robotic movement.

-

Sanchez focuses on clothing that empowers people with disabilities by being both functional and stylish.

At SEAS, fashion-designer-turned-engineer Vanessa Sanchez contributed to the development of a textile-based actuator that uses resistance heating, rather than pneumatics, to enable soft robotic movement. Credit: Wyss Institute at Harvard University

As a young child, Vanessa Sanchez had a habit of taking things apart and trying, often unsuccessfully, to put them back together. Seeking to channel her daughter’s unbridled creativity into a less destructive pursuit, Sanchez’s mother bought the 8-year-old a sewing machine.

“Sewing immediately appealed to me because it was a creative space where I could think of different shapes or styles and try to put different materials together into unique configurations,” said Sanchez, a Ph.D. candidate at the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences and Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. “Going from something that is an idea or a sketch through the process to make it into a garment was exciting to me.”

Her interest in sewing quickly morphed into a full-blown passion for fashion design that led the Long Island, N.Y., native to enroll in Manhattan’s Fashion Institute of Technology. Eyes set on a career in New York’s glamorous fashion scene, Sanchez dove into lessons on garment construction, pattern making, draping, and fashion illustration with avid enthusiasm.

The technical side of clothing development appealed to Sanchez during her studies at Manhattan’s Fashion Institute of Technology. (Photo provided by Vanessa Sanchez)

She was drawn to the technical side of clothing development, especially the iterative process of making a garment from nothing more than a faint notion of a potentially interesting color or pattern. But digging into fashion soon taught Sanchez that the field lacked the depth she sought.

“I wanted to make clothing that could do something more for people. I didn’t know exactly what that was yet, but I felt that I needed a deeper understanding of the materials to innovate in the way I intended.”

So Sanchez transferred to Cornell University and enrolled in the fiber science program. There, she studied the chemistry and engineering of fibers, textiles, and dyes.

While the organic chemistry and computer science classes were a departure from fashion school that pushed Sanchez to her limits, this coursework felt more fulfilling. She joined a lab to work on an electrospinning project and found, in research, the ideal way to use her skills and passions to help people.

Sanchez worked to develop nanofiber mats for cloth facemasks that could effectively capture harmful microbes while allowing an individual to breathe easily through the mask.

“I loved that, in research, not everything is known or set. We are exploring something new, and I felt the same way I had with some of the fashion designs I was making,” she said. “With fashion, I would think ‘no one has ever made a coat that has looked like this before. I don’t even know if it’s going to work, but I’m going to try it.’ I saw so many parallels to research.”

A garment Sanchez designed for method 6, a collection that parallels the contradicting similarities between the process of creation in punk and research.

After traveling to Luxembourg to work on liquid crystal core nanofibers that could change color based on an individual’s skin temperature, she felt that the pull of a research career was too strong to resist.

Sanchez accepted a job as a research fellow in the lab of Conor Walsh, Gordon McKay Professor of Engineering and Applied Sciences, and worked on a soft, wearable robotic device aimed at improving mobility for people who have suffered injuries or strokes.

From there, she joined the labs of Walsh and George Whitesides, Woodford L. and Ann A. Flowers University Professor, as a materials science and mechanical engineering graduate student. Her work in the Whitesides lab focuses on chemistry and materials, while in the Walsh lab, Sanchez studies sensing and wearable robotics.

She recently contributed to the development a textile-based actuator that uses resistance heating, rather than pneumatics, to enable soft robotic movement. She also helped develop a textile-based sensor that could measure the degree of actuation, enabling closed-loop control.

Looking to the future, Sanchez is interested in focusing on smart textile-based systems that respond to their environment. Smart textiles could go a long way toward assisting people, from robotic gloves that help people after stroke grip items to garments that can automatically warm or cool people with spinal cord injury, many of whom struggle with thermal regulation.

“A lot of these people may not have the mobility to just roll up their sleeves or unzip their jacket very easily, so making a fabric that responds to the person and their environment would be very useful,” she said. “But I also want to focus on reducing the stigma we sometimes see around clothing for people with disabilities. People don’t want to wear something that looks like it belongs in a hospital.”

Sanchez is exploring this technology as a volunteer with Open Style Lab, where she works with engineering undergrads and fashion designers to develop garments that help people with limited mobility overcome daily challenges.

Sanchez (top row, left) at the Open Style Lab, where she works with engineering undergrads and fashion designers to develop garments that help people with limited mobility overcome daily challenges. (Photo provided by Vanessa Sanchez)

She enjoys the opportunity to combine fashion and science in a way that could empower these people to live more independent lives.

“From the beginning, I wanted to make clothing that did more for people in some way,” she said. “I didn’t think science and fashion could have anything in common, but now I’m seeing it all come together. I am grateful that I can do this kind of work.”

Developments in wearable robotics

Explore more research on soft robotics for mobility enhancement at Harvard SEAS.

Press Contact

Adam Zewe | 617-496-5878 | azewe@seas.harvard.edu