News

Chef Freddie Bitsoie stirs fresh ingredients into his hominy stew. (Photo by Joshua Chiang/SEAS Communications)

Many Native American recipes, passed down by word of mouth for generations, are steeped in history. But these storied dishes also showcase science, as community members learned during a recent public lecture.

The presentation featured Chef Freddie Bitsoie, 2013 winner of the Native Chef Competition at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian.

The lecture, part of a series organized by Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS), is based on the undergraduate course “Science and Cooking: From Haute Cuisine to the Science of Soft Matter (GenEd 1104).”

Fittingly, Bitsoie’s lecture, which was titled “Hominy and Posole: The Science of Native American Cooking,” fell on Indigenous People’s Day.

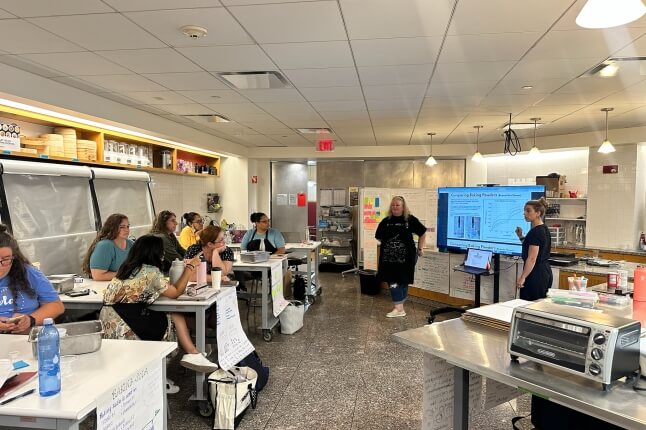

Lecture attendees are able to watch a close-up of Chef Bitsoie's technique on the big screen. (Photo by Joshua Chiang/SEAS Communications)

Since his undergraduate studies in anthropology, Bitsoie has been interested in central aspects of culture. During his senior year, an instructor encouraged him to explore food as a discipline, an exploration that inspired Bitsoie to ultimately enroll in culinary school. He is passionate about Native food and sharing lessons from Native cooking in an entertaining way.

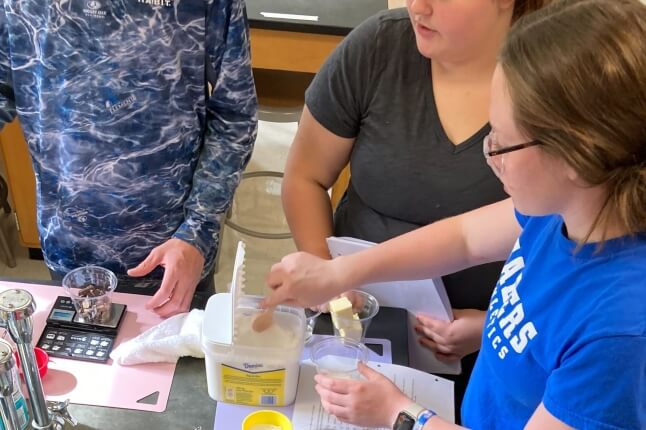

Using a recipe commonly made during Christmas or New Year’s celebrations, Bitsoie prepared posole, a hominy stew and one of the oldest continuously made dishes in human history. Hominy is corn treated with alkali, which gives it a meaty flavor. This treatment is an example of diffusion, which was the scientific theme of this lecture. Diffusion is the movement of one substance into another substance, such as alkali moving into the corn.

Pia Sörensen, Senior Preceptor in Chemical Engineering and Applied Materials and GenEd 1104 instructor, described how molecules are like people in a crowded place, moving and pushing against each other in all different directions. In math, the average movement of a molecule over time is called a random walk and can be characterized by the diffusion equation, which depends on the diffusion coefficient of the material and the time that passes.

“I appreciate how the lecture focused on one specific ingredient. Focusing on one element makes the science more accessible,” said audience member Kyisha Davenport.

Attendee Tallen Sloane asks Chef Bitsoie how he comes up with his menu. (Photo by Joshua Chiang/SEAS Communications)

To complement the scientific themes in cooking, Bitsoie shared his thoughts on both the historical significance and deeply personal nature of food.

“Native people have taken care of their food continuously over time. We built it, we didn’t make it,” he said.

In Bitsoie’s view, Native food is all about storytelling, and the history of Native food has shaped its unique story. He sees a fundamental difference between Native and European recipes. He finds that the European model tends to rely on having very specific ingredients, while Native cuisine has a different mindset and spirit of cooking. The recipes do not rely on specific ingredients because, historically, so many factors could influence the availability of those ingredients. Recipes for Native cooking highlight the ingredients at hand.

On a personal level, Bitsoie sees food as an essential component of identity.

“There are only two things that will offend you personally if attacked: your name and your comfort food, because those are at the core of who you are,” he said.

Bitsoie, who is chef at the Mitsitam Native Foods Café in the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C., is passionate about respecting and sharing foods across cultures.

“We learn so much more through our food than through anything else,” he said.

Topics: Cooking

Cutting-edge science delivered direct to your inbox.

Join the Harvard SEAS mailing list.

Press Contact

Adam Zewe | 617-496-5878 | azewe@seas.harvard.edu