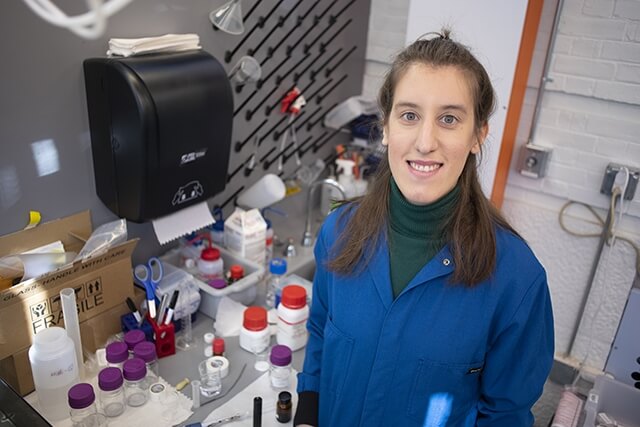

Grad student Eleni Dovrou studies the formation and chemical behavior of particulate matter. (Photo by Eliza Grinnell/SEAS Communications)

Eleni Dovrou’s initial interest in environmental science and engineering was triggered on the beach volleyball court.

Born into a family of athletes (her father ran and coached track, her mother was a ballerina and gymnast, and her sister competes in track and field), Dovrou began playing volleyball at age 5 in her native Greece. She excelled at the sport and, by the time she was a teenager, five-foot-10-inch Dovrou was playing at a high level.

“As a beach volleyball team, we traveled a lot. I had always been captivated by the beauty of the environment, but I realized that, in visiting a lot of beaches, the sea was often so polluted that we couldn’t even walk into it and the sand was so dirty it was dangerous to play in,” she said. “Initially, I wanted to make a difference and help improve the environment to provide nice facilities where we could play volleyball.”

So Dovrou decided to study environmental engineering as an undergraduate at the Technical University of Crete.

Interested in research, she began working in the lab of a professor who was studying the chemical properties of nanomaterials that could trap tiny pollutants in seawater. Dovrou explored the stability of these nanoparticles to determine whether they would break down later and release the hazardous chemicals back into the water.

“I became fascinated by the idea that I could actually find something that nobody else has found before,” she said. “It was exciting to reproduce what is happening in an aquatic system or in the atmosphere and see how those compounds actually behave.”

Dovrou's initial interest in environmental science and engineering began with her desire to improve the environment to create better facilities for beach volleyball. (Photo provided by Eleni Dovrou)

Hooked on research, Dovrou decided to pursue a Ph.D. in environmental science and engineering at the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences and the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, where she joined the lab of Frank Keutsch, Stonington Professor of Engineering and Atmospheric Science.

She changed gears in the Keutsch lab, focusing her research on atmospheric pollution. She applied her background studying aquatic systems as she explored the formation and chemical behavior of particulate matter.

Dovrou studies atmospheric sulfur compounds that are produced by oxidation of dissolved sulfur dioxide with multifunctional organic hydroperoxides in cloud droplets, under conditions with and without anthropogenic influence. These reactions result in the formation of sulfate, which contributes to acid rain or stays in the atmosphere, where it contributes to fine particulate matter. Fine particulate matter is important for climate and has significant effects on human health, she explained.

“These reactions are favored under conditions without anthropogenic influence, and are important for the sulfur budget (the total amount of sulfur in the atmosphere),” she said.

For her thesis, Dovrou is collaborating with Jean Rivera-Rios, a former graduate student in the Keutsch group, and Kelvin Bates, a postdoctoral fellow in the lab of Daniel Jacob, Vasco McCoy Family Professor of Atmospheric Chemistry and Environmental Engineering, to synthesize these hydroperoxides and model the formation of sulfate. The collaborators hope to better understand how and why the atmospheric concentrations of the compounds change on a regional and global scale.

Dovrou and her collaborators hope to better understand how and why the atmospheric concentrations of hydroperoxides change on a regional and global scale. (Photo by Eliza Grinnell/SEAS Communications)

Since these multifunctional organic hydroperoxides are formed by isoprene, a compound emitted by plants, the researchers have seen high contributions in the Amazon rainforest, which they expected, but also in the southeastern United States, which was a surprise.

“If we understand these pathways, we can get a better sense of how much sulfate is in the atmosphere,” she explained. “This has implications because, where we form more sulfate, we will have more acidic rain and influence the distribution of sulfate particulate matter. Sulfate production could also be important for the formation of new particles. Particles can act as cloud condensation nuclei around which cloud droplets are formed, which influences their properties.”

But before Dovrou and her collaborators can study these hydroperoxides, they have to create them. The chemicals aren’t stable enough to be commercially available and synthesizing them in a laboratory involves delicate experiments and plenty of trial and error.

And once they create chemicals to study, they need to develop a method that measures sulfate with accuracy, she explained. It is very challenging to actually represent what happens in the atmosphere, since the chemical concentrations are so low, and there are multiple reactions under different pH conditions.

Dovrou is now hoping to take this research one step further and begin investigating how these particles impact human health.

For instance, since these chemicals react differently in liquid-based environments, Dovrou is interested in exploring what happens when they interact with the liquid inside the lungs, or in other areas of the human body.

“The opportunity to make a difference inspires me a lot, especially on those tough days. As experimentalists, things don’t work out all the time,” she said. “In the future, this work could help us understand the chemistry and thus the pathways required in reducing the pollution in the environment and help improve human health. That drives me.”

Dovrou has found that in research, just like on the beach volleyball court, working together is the best way to achieve success. (Photo provided by Eleni Dovrou)

And she expects it to continue to drive her in the future. Dovrou hopes to remain in academia and focus on combining her atmospheric research with clinical studies through new collaborations.

In the Keutsch Group, she’s found that in research, just like on the beach volleyball court, working together is the best way to achieve success.

And while she finds the opportunity to focus on academic research exciting, Dovrou also wants to use her position to pay it forward and give opportunities to students who are interested in pursuing research.

“A lot of people told me I wouldn’t get into Harvard,” she said. “It is a reward and honor to be able to work here, and I want people to know that nothing is impossible.”

Press Contact

Adam Zewe | 617-496-5878 | azewe@seas.harvard.edu