Andrew Bosworth, A.B. '04 (computer science) is vice president of augmented and virtual reality at Facebook.

It would seem like Andrew Bosworth’s computer science chops are what got him to where he is today: vice president of augmented and virtual reality at Facebook.

But he’ll be the first to say that curiosity and open-mindedness played a much more important role in his journey to—and through—the global tech behemoth.

As a kid living on a farm outside San Jose, Calif., Bosworth’s first introduction to the world of computer science came from video games he loved to play on his family’s Apple IIe.

“As I continued to play video games, I became increasingly fascinated by the non-player characters,” recalled Bosworth, A.B. ’04, a computer science concentrator at the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences. “For instance, in an airplane fighting game, how did they get the airplanes to fly realistically?”

Bosworth’s transition from gamer to developer was sparked through the agricultural youth development program 4-H. He made friends with a club member who taught him to program in QBasic. They would work together after school, writing programs to change the color of the computer screen or move a cursor.

Those experiences inspired Bosworth to take a computer science class in high school, where he was immediately drawn to the creativity afforded by the field, and energized by how quickly he could see the results of his work—a boon for a kid with a short attention span.

He arrived at Harvard dead-set on studying computer science, and enjoyed the challenges of Introduction to Computer Science (CS50) and Abstraction and Design in Computation (CS51).

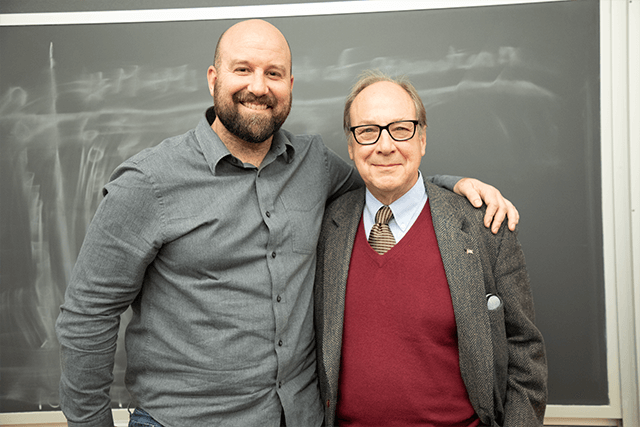

Bosworth with one of his former Harvard computer science professors, Harry R. Lewis, Gordon McKay Professor of Computer Science. (Photo by Adam Zewe/SEAS Communications)

The strong community he encountered in those courses, and the student course assistants who helped him overcome increasingly complex coding challenges, inspired him to teach.

While serving as a teaching fellow for Artificial Intelligence (CS182), he met then-undergraduate Mark Zuckerberg.

“Facebook came out on February 12, which was two weeks after finals ended for CS182, so he was clearly working on Facebook instead of studying for my class,” recalls Bosworth, laughing. “Clearly, Mark was a guy who was building things, but none of us had any idea what Facebook would become.”

After graduation, Bosworth began working as a programmer at Microsoft where he learned a great deal about what it meant to be a professional software engineer.

Settling in for a rewarding career at Microsoft, Bosworth was taken by surprise when he received an AOL instant message from a recruiter inviting him to interview for an artificial intelligence role at Facebook.

A skeptical Bosworth flew to the Bay Area for the interview, planning to use the time to check in with family and talk to some old classmates.

“I didn’t take it that seriously,” he recalled. “It wasn’t until the interview that I realized the scope and the ambition of what they were doing, and what it could become. I got pretty excited about it after that.”

But Bosworth was still reluctant to give up his career at Microsoft to embark into the unknown at a startup.

“One of the greatest gifts my manager gave me, when the opportunity to join Facebook came up, he said to me: ‘You’ve got to go. I hate to lose you, because you’re a great talent here, but you are young, you’ve got nothing to lose, and you’re going to learn a ton in that environment,’” Bosworth said.

He took his manager’s advice and became one of the fledgling company’s first dozen engineers on staff.

Bosworth developed what would later become the Facebook News Feed, building infrastructure as a back-end engineer. He also co-invented Messenger, Groups, and worked on early anti-spam and anti-abuse systems. The platform had 5 million users when he joined—in less than a year, that user base more than doubled and the growth was exponential from there.

To keep up, the team worked at a breakneck pace in those early days. And the lines between work and home weren’t just blurred, they didn’t exist. Bosworth had six roommates and all were Facebook employees, so they worked constantly. But it didn’t really feel like work, he said. They enjoyed the fun of taking risks, being creative, and trying new, and sometimes crazy, things.

“I don’t think any of my code has survived the thousand-fold scaling of Facebook, but a lot of the systems are still in place,” he said. “The way it was then, no one did just one thing. We all built a ton of different features all the time. We were constantly thinking of things we’d like to try, and some of them worked and some didn’t.”

While that creativity made the environment fun, the massive popularity of Facebook and ever-evolving technology created frequent challenges.

For instance, he and his colleagues often encountered acute memory shortages and bandwidth limitations and had to come up with workarounds for machinery shortcomings. The first version of News Feed wasn’t real time, he recalled—it was stored in memory and built for each user every 30 minutes.

“I had to build a system that would constantly check to make sure it was running, and if it wasn’t running, it would call my phone and wake me up in the middle of the night, and I would have to fix it,” he said. “Things are a lot easier today than they were then, but at the same time, there was something quite satisfying about it. I built every part of that system, and understood how every little piece of that system worked.”

Bosworth shares tech insights during the Harvard Business School's annual tech conference, "Iteration: Shaping the Next Decade."

More than a dozen years later, things have changed at Facebook, and Bosworth’s role has morphed, too. He and his coworkers are still trying to create a set of tools that don’t exist, but they are now delving much deeper than they did before.

Bosworth leads the company’s charge into augmented and virtual reality, a brave new world for the social networking site, and the source of a completely different set of challenges.

“Now, we are looking at hardware on the consumer level and trying to build into form factors like glasses,” he said. “Glasses don’t struggle with Moore’s law; they struggle with the first law of thermodynamics. The problem isn’t that I can’t get enough transistors onto your glasses—the problem is, when I do, it will burn your face.”

In augmented and virtual reality, the input methods and application models programmers have relied on for 60 years fall flat, so every question they try to answer is a new one, he said. Enabling people to interact with virtual environments without a mouse, keyboard, or other precise pointing equipment is a major hurdle, as is enhancing artificial intelligence so it can make strong inferences about the world.

Facebook’s Spark AR Studio is helping the company better understand how to improve the technology for the future, he said. The platform is being used by hundreds of millions of people each month, and while “growing” an augmented reality beard might not seem like serious research, the application is helping the company track and solve important problems.

“It is a very exciting time. And it feels immense and challenging, but at the same time, it does feel kind of inevitable. We really believe this is the next frontier of computing,” he said. “Instead of cell phones, people will one day have a constellation of augmented reality devices on their person. But the path from here to there isn’t at all clear to us or to anybody else, so we have to invent it and that is exciting.”

The worlds of augmented and virtual reality may be about fun and games now, but Bosworth envisions a future where those tools are used to unlock opportunities for a global workforce.

People often make decisions about the college they go to or the company they join based on geographic, social, or economic factors, he said. If that wasn’t an issue—if people could learn and work just as effectively using augmented and virtual reality—human capital could be allocated much more efficiently around the globe.

For Bosworth, it’s a mind-blowing future that he couldn’t have imagined when he joined the nascent social networking company.

“None of us imagined what Facebook would turn out to be,” he said. “Working there feels like a privilege and responsibility, and you can’t question that we’ve had an impact. What we’re working on now is just to continue to sharpen that impact and make sure it is a positive one.”

Looking back, Bosworth feels grateful for the opportunities he’s had along the way, and the lessons that have helped him achieve success as both a technologist and a leader.

“It is hard to look past the fact that a lot of skills I use today have nothing to do with computer science. It is valuable to my team that I speak the language, but the skills I use today are about managing people and relationships, and about communicating vision really clearly,” he said. “Years ago, I really thought I wanted to program AI for video games. So keeping a broad view and open mind is the best thing you can do for yourself. Give yourself that space to follow what you are curious about.”

Press Contact

Adam Zewe | 617-496-5878 | azewe@seas.harvard.edu