News

CAMBRIDGE, Mass. – June 28, 2010 – "More than meets the eye" may soon become more than just a tagline for a line of popular robotic toys.

Researchers at Harvard and MIT have reshaped the landscape of programmable matter by devising self-folding sheets that rely on the ancient art of origami.

Called programmable matter by folding, the team demonstrated how a single thin sheet composed of interconnected triangular sections could transform itself into a boat- or plane-shape—all without the help of skilled fingers.

Published in the online Early Edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) during the week of June 28, lead authors Robert Wood, associate professor of electrical engineering at the Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS) and a core faculty member of the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering, and Daniela Rus, a professor in the Electrical Engineering and Computer Science department at MIT and co-director of the CSAIL Center for Robotics, envision creating "smart" cups that could adjust based upon the amount of liquid needed or even a "Swiss army knife" that could form into tools ranging from wrenches to tripods.

"The process begins when we first create an algorithm for folding," explains Wood. "Similar to a set of instructions in an origami book, we determine, based upon the desired end shapes, where to crease the sheet."

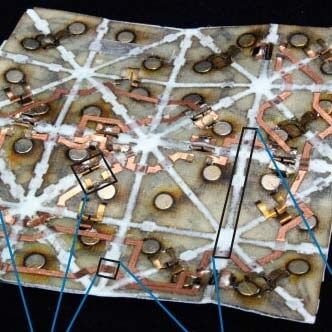

The sheet, a thin composite of rigid tiles and elastomer joints, is studded with thin foil actuators (motorized switches) and flexible electronics. The demonstration material contains twenty-five total actuators, divided into five groupings. A shape is produced by triggering the proper actuator groups in sequence.

To initiate the on-demand folding, the team devised a series of stickers, thin materials that contain the circuitry able to prompt the actuators to make the folds. This can be done without a user having to access a computer, reducing "programming" to merely placing the stickers in the appropriate places. When the sheet receives the proper jolt of current, it begins to fold, staying in place thanks to magnetic closures.

"Smart sheets are Origami Robots that will make any shape on demand for their user," says Rus. "A big achievement was discovering the theoretical foundations and universality of folding and fold planning, which provide the brain and the decision making system for the smart sheet."

The fancy folding techniques were inspired in part by the work of co-author Erik Demaine, an associate professor of electrical engineering and computer science at MIT and one of the world's most recognized experts on computational origami.

While the Harvard and MIT engineers only demonstrated two simple shapes, the proof of concept holds promise. The long-term aim is to make programmable matter more robust and practical, leading to materials that can perform multiple tasks, such as an entire dining utensil set derived from one piece of foldable material.

"The Shape-Shifting Sheets demonstrate an end-to-end process that is a first step towards making everyday objects whose mechanical properties can be programmed," concludes Wood.

Movie and Images for Download

All courtesy of Robert Wood, Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, and Daniela Rus, MIT.

Movie: A programmable sheet self-folds into a boat- and into a plane-shape.

Figure 1: Self-Folding Sheet Up-Close. Fig. 1. 32-tile self-folding sheet, capable of achieving two distinct shapes: a “paper airplane” and a “boat.” Joule-heated SMA bending actuator “stapled” into the top (A) and bottom (B) sides of the sheet. Patterned traces cross the silicone flexures and are shown unstretched (C) and after stretching as a flexure bends 180° (D). Silicone flexure bent 180°, with both a single fold (E) and folded again to create a compound fold (four layers thick) (F).

Figure 2: Crease Patterns: Simulation (left) and experiments (right, with time shown in lower right) of a self-folding “boat.”(A). All actuators receiving current B). Immediately before magnetic closures engage (C). Finished boat on side (D).

###

Wood and Rus's co-authors included Elliot Hawkes and Hiroto Tanaka, both at Harvard, and Byoung Kwon An, Nadia Benbernou, Sangbae Kim, and Erik Dermaine, all at MIT.

The authors acknowledge funding from the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA).

Topics: Robotics, Electrical Engineering

Cutting-edge science delivered direct to your inbox.

Join the Harvard SEAS mailing list.

Scientist Profiles

Robert J. Wood

Harry Lewis and Marlyn McGrath Professor of Engineering and Applied Sciences