News

Fourth-year mechanical engineering student David Andrade chisels a block of wood for the 22-foot-long Japanese wooden boat constructed during a winter session workshop at the Harvard Edwin O. Reischauer Institute of Japanese Studies. (Matt Goisman/SEAS)

As chief engineer for the Harvard Satellite Team, fourth-year mechanical engineering student David Andrade works mostly with metal and electrical wiring. But he had few opportunities to work with wood through his first three-plus years at the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS).

“The essence of building is what intrigues me,” Andrade said. “I enjoy the process of making things.”

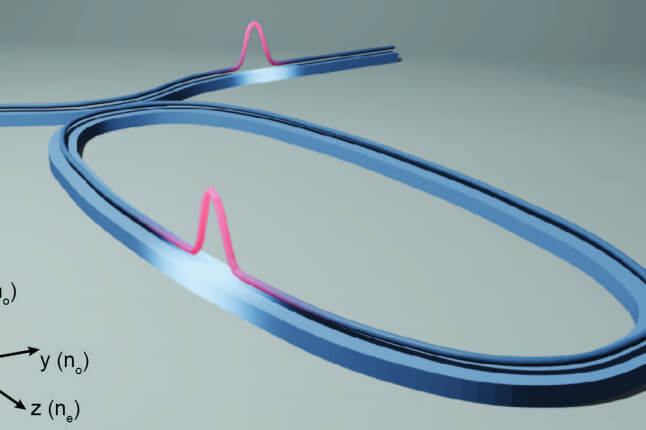

That interest and a desire to learn some new skills inspired Andrade to join several SEAS students during winter session to build a 22-foot-long Japanese wooden boat known as a honryōsen. The 10-day workshop was offered by Harvard’s Edwin O. Reischauer Institute of Japanese Studies (RIJS). The hand-built boat, now on display as part of the RIJS 50th anniversary exhibition, “In the Making: Wasen and Lessons in Japanese Wooden Boatbuilding,” will be launched on the Charles River later this spring.

“It was amazing,” said Hana Wakamatsu, a fourth-year applied math concentrator at SEAS. “You don’t really know what the boat will look like when you start with two planks, and then you end up with this boat.”

Andrade, Wakamatsu and third-year mechanical engineering concentrator Kade Kelsch represented SEAS in the workshop. Traditional Japanese boats are made of just wood and nails, sawed and assembled tightly enough that additional sealants and caulking aren’t necessary. Students used hand saws and other handheld tools to carve most of the parts.

Third-year mechanical engineering concentrator Kade Kelsch works with a hand saw. (Matt Goisman/SEAS)

“Working with your hand tools, you have to do it for so much longer,” Andrade said. “So, if you’re doing a certain kind of cut into the wood, you’re not going to stand there for five hours doing the same cut. You’re going to listen to your body to try to find the most efficient way to cut. You’re going to listen to how the saw moves. Working on this project has made me more open to attention to detail and finding the best way to make something.”

For Kelsch, one of the biggest differences from her SEAS education was the lack of preexisting plans. Participants learned how each part should be built, then went to work. As parts were completed, fine alterations became necessary to make sure each part fit.

“In mechanical engineering, when you assemble or make things in the machine shop, you have a blueprint,” Kelsch said. “You make something as exact to that blueprint as possible, and if everything is made perfectly, it’ll all come together. The Japanese boatbuilding method is that you don’t have a blueprint, but as you’re making it, you fit each part uniquely to what it needs to fit into.”

Kelsch came into the workshop with some prior carpentry knowledge and an interest in Japanese language and culture. Wakamatsu had “never touched a chisel in my life,” but as a violin player had seen the assembly of many wooden instruments. Along with Andrade, all three finished the workshop with some new skills to augment their engineering education.

David Andrade uses a band saw. (Matt Goisman/SEAS)

“I learned some new carpentry skills that I never had, and I also learned a lot about Japanese culture and the way that traditional crafts are passed down,” Kelsch said. “Every time we talked about traditional masters and apprentices, it sounds like such a hard thing to do, but it always makes me want to do it.”

This was the first time RIJS offered a large-scale construction workshop. It was taught by professional boatbuilder Douglas Brooks. Japanese flat-bottomed skiffs were frequently used to transport rice harvests down rivers prior to World War II, when industrialization and drainage reduced the need. Some fishermen continue to use the boats to this day.

“Gaining an intuition for how building works, just by being hands-on and stepping away from the analysis, has given me a better perspective on how to make things,” Andrade said. “You don’t need machines or mills to make very precise things. These are very precise techniques. It takes a lot longer, but it accomplishes the same result.”

Photo of the finished boat by Martha Stewart.

Topics: REEF Makerspace, Materials Science & Mechanical Engineering

Cutting-edge science delivered direct to your inbox.

Join the Harvard SEAS mailing list.

Press Contact

Matt Goisman | mgoisman@g.harvard.edu