News

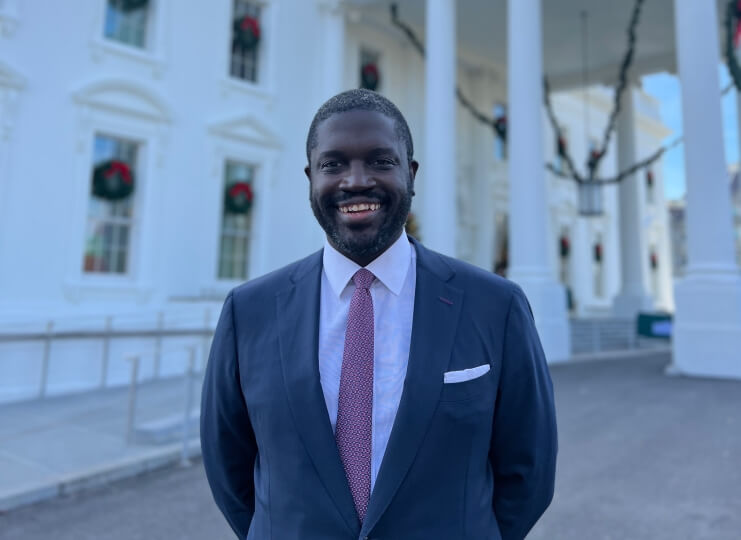

Nana Menya Ayensu, S.B. '07

Nana Menya Ayensu, S.B. ‘07, witnessed first-hand how disruptive a lack of energy can be on a population. He moved from Washington, D.C., to Ghana during middle school, and didn’t return to the United States until he began college at Harvard. That switch meant going from a nation where electricity is almost always available, to one where the demand for electricity often exceeded the capacity of the nation's energy infrastructure.

“Spurring economic growth, providing quality healthcare and education, so many of the big developmental outcomes you’d want a society to deliver, are really fueled by energy,” Ayensu said. “My first year in Ghana, the country was going through a major drought. A lot of our power was coming from hydroelectricity, which is generally low cost, clean, and reliable. However as the water levels in the dams dropped to critical levels, that led to a ton of mandatory load-shedding. There were periods where we’d have 12 hours on, 24 hours off for electricity, on top of random, intermittent outages.”

Those experiences remained with Ayensu as he pursued his concentration in mechanical engineering at the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS). While he initially planned to work in aviation or automobile manufacturing, that all changed when internships in Japan took him on tours of large power stations and wind farms. Combined with coursework on thermodynamics, he realized working on energy infrastructure could have a more direct impact on society.

“We talk a lot about resiliency and energy independence in the U.S. now, but if you go around Ghana and similar nations, you’ll find that most businesses and many homes have backup generators or solar panels on their roofs with batteries,” he said. “That not only cuts their costs, but also provides backup power and resiliency. It’s a top-of-mind consideration instead of what you take for granted.”

For a senior thesis at SEAS, Ayensu worked with then-visiting professor Shriram Ramanathan to explore nanoscale, superionic fuel cell materials and design an “electric nose,” a solid-state sensor that could rapidly detect the presence of hydrogen. He went on to obtain a master’s degree in materials science at Stanford, and he’s still working in the energy sector 15 years after leaving Cambridge — just on a much larger scale.

Ayensu is a Special Assistant to the President for Climate Policy, Finance, and Innovation and part of the White House Climate Policy Office (CPO), where he focuses on power sector decarbonization and climate technology investment.

It’s both the coolest job I’ve ever had, and at the same time the scariest. You really feel this huge, palpable opportunity to have an impact.

"On any given day, I might be talking to CEOs about new businesses they’re trying to get off the ground, local or international governments about potential collaborations, technology companies, financial investors, climate advocates, climate protesters, and an incredible variety of other stakeholders," he said. "There are all these different interests that we have to find a way to harmonize.”

Ayensu has always been interested in technology, business, and infrastructure, and every step in his career has featured some combination of all three. After graduating from Harvard, Ayensu worked at the intersection of technology, business and economics at different companies, including GE’s energy R&D and investment groups; Uptake, an industrial AI software provider; ENGIE Impact, a sustainability consulting firm; and Sidewalk Infrastructure Partners, which builds technology-enabled infrastructure investment platforms.

“All my career adventures have highlighted the importance of government policy in driving the more ambitious transformations we need,” he said. “The government can think about what needs to happen technically, financially, politically and scientifically in order to get something done. In this next wave of energy transition, a lot of the impacts we’re going to see in the next 10-20 years will stem from decisions made at this time. I thought it would be an incredible opportunity to lean in and help shape that future.”

Helping to decarbonize the U.S. power sector is critical to Ayensu’s agenda, not just because it’s one of the largest sources of emissions, but because power unlocks potential reductions in so many other industries. More electric vehicles would reduce carbon emissions from the automotive sector, for example, but that will increase demand for electricity. That demand could be met with a more sustainable electric grid. And while such a transition might be expensive, not acting now will ultimately cost much more.

“We’ve already set a record for the most billion-dollar natural disasters in a single year in U.S. history, with total economic damages well above $200 billion, and that’s part of a longer-term trend which has been moving upward,” Ayensu said. “Climate risk isn’t something you can ignore. The effects are happening right now in very tangible ways that cost real money. The droughts, wildfires, storms, and floods are all becoming more frequent and larger, and their socioeconomic impacts are bigger, so the impetus to act and embrace the bigger challenges of climate mitigation and adaptation should be bigger too. No matter what, this is going to cost money. It’s a question of where you want your money to go, and also whether we want the world to benefit from building new economies along the way.”

As he helps the U.S. invest in new climate tech and decarbonization strategies, Ayensu still draws on concepts he learned at SEAS. Understanding thermodynamics and chemistry makes it easier for Ayensu to assess the viability of potential energy sources, while studying materials science and electrical engineering taught him how solar panels and batteries work, and computer science and math have enabled him to design solutions to optimize complex systems and analyze markets. And because Harvard is so interdisciplinary, studying there taught Ayensu how to approach multifaceted challenges such as climate change, sustainability, affordability, and resiliency.

“Being able to explain these concepts on a daily basis to different kinds of people with different backgrounds, and doing so through multiple formats and media, is a skill that’s really served me well,” Ayensu said. “It’s allowed me to successfully navigate different environments.”

Topics: Alumni, Climate, Materials Science & Mechanical Engineering, Undergraduate Student Profile

Cutting-edge science delivered direct to your inbox.

Join the Harvard SEAS mailing list.

Press Contact

Matt Goisman | mgoisman@g.harvard.edu