News

A new student organization at the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS) wants to make it easier for undergraduates to get involved with biological research. Collaborating with the Active Learning Labs at the Science and Engineering Complex in Allston, OpenBio’s goal is to make biological research projects as easy to pursue as building something in the nearby engineering Makerspaces.

“Especially at the undergraduate level, if someone wants to pursue an idea they have for a biological research project, the only avenue they really have is to join an academic lab,” said OpenBio co-president Benjamin Chang, a third-year computer science and chemical and physical biology concentrator. “As biology is becoming more democratized, we want to enable anyone to do incredible science at any level regardless of whether they have an academic lab affiliation or not. We provide the funding, space, resources and advising to help turn students’ research vision into reality.”

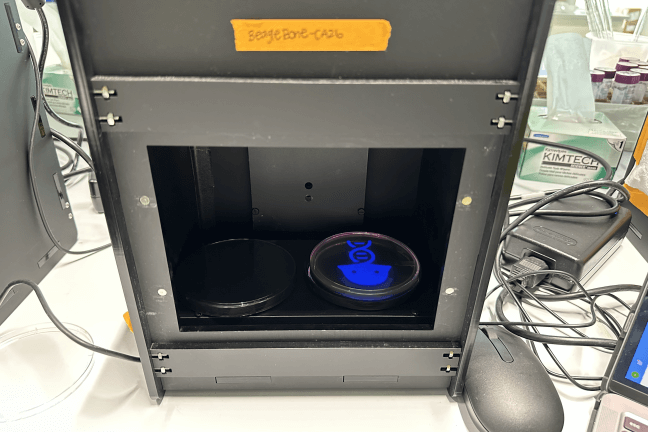

OpenBio held its first workshop at the end of the Fall 2022 semester. Ten students spent a Sunday at the SEC environmental engineering labs creating art from bacteria. They learned basic wet lab techniques such as pipetting volumes of liquid and preparing slides, then created petri dishes of non-pathogenic E. coli bacteria which had been engineered to produce a color when exposed to blue light. Using blue light projectors, students were able to stain images onto their dishes such as the head of a dragon, outline of a cat, or a heart.

“It’s pretty similar to how traditional photography works,” said co-president Izzy Goodchild-Michelman, a third-year studying molecular and cellular biology. “You can imagine a petri dish coated with a film of millions of E. coli. We engineered them using optogenetics so if they’re hit with a certain color of light, they’ll then produce a pigment that stains the dish that same color. Because there are so many E. coli on the plate, we’re able to create high-resolution images.”

A blue light emitter projects an image onto a petri dish, causing the E. coli bacteria to produce a pigment matching the design. (Harvard OpenBio)

Examples of bacterial art designs produced at a Harvard OpenBio workshop at the Science and Engineering Complex. (Harvard OpenBio)

Because the workshop only had a limited number of incubators to develop the images, attendance was limited to 10. The event was popular enough to create a waitlist, so OpenBio plans to run the workshop again this semester.

“Over half the participants were not from a traditional wet lab concentration, so it’s cool they were interested in coming,” said Goodchild-Michelman. “The level of enthusiasm was very high. E. coli needs 24 hours to grow and process the print, and I was happy that almost every participant wanted to come back out to the SEC and pick up their plate the next day. ”

The end product might be a Petri dish stained with a picture of a beaver. But underneath a seemingly simple process are some advanced bioengineering techniques such as optogenetics, in which cells are engineered to be light-sensitive.

“A lot of the stuff that we actually did is very complex,” Chang said. “To have bacteria that can respond to colors and light and secrete different proteins is fundamental to synthetic biology. It’s cool to have people both learn how to use a pipette and these cutting-edge techniques in the span of a couple hours.”

As a computer science student, Chang has spent plenty of time in the SEC. But for students like Director of Engagement Audrey Gunawan, who’s studying molecular and cellular biology and government, this was her first time at the SEC.

“I was immediately wowed by the space when I walked in,” Gunawan said. “It’s super beautiful, super new, and it’s very clear that it’s a space meant for collaboration and for students to pursue what they’re interested in.

“The openness of the space really helped our Engagement team plan this workshop, especially since it required a lot of preparation beforehand. We wanted to make the procedure go as smoothly as possible, so that students with little to no wet lab experience would feel comfortable,” Gunawan said.

Goodchild-Michelman added, “We’ve had students reach out and say they want to get more involved in bioengineering. We’ve increasingly been trying to point them to the amazing academic courses offered in the new bioengineering and environmental engineering spaces.”

Students work on their bacterial art design at the Harvard OpenBio workshop at the Science and Engineering Complex. (Harvard OpenBio)

A student practices pipetting volumes of liquid at an OpenBio workshop at the Science and Engineering Complex. (Harvard OpenBio)

With its inaugural event now in the past, OpenBio is planning a much more challenging project for Spring 2023: using the fermentation properties of dairy to create an anti-tuberculosis probiotic.

“It’s going to be a community project in which students from both SEAS and the general Harvard community will come together and try to create this anti-tuberculosis therapy using the principles of synthetic biology to try to create something more cost-effective than current therapies,” Chang said.”

OpenBio currently has over 100 members, including 14 board members. Its faculty advisor is David Mooney, Robert P. Pinkas Family Professor of Bioengineering, and it’s also advised and supported by SEAS Active Learning Labs staff Melissa Hancock, Nicholas LoRusso, and Avery Normandin.

“We want people to realize that there are so many amazing things you can build with biology these days,” Chang said. “We want to create a community of incredible researchers at Harvard.”

Topics: Bioengineering, Student Organizations

Cutting-edge science delivered direct to your inbox.

Join the Harvard SEAS mailing list.

Press Contact

Matt Goisman | mgoisman@g.harvard.edu