News

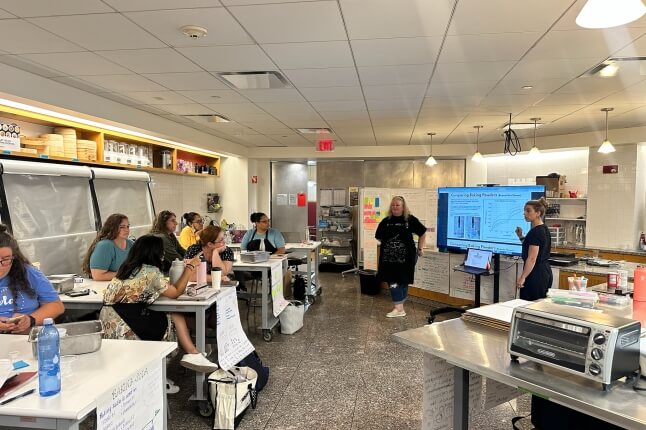

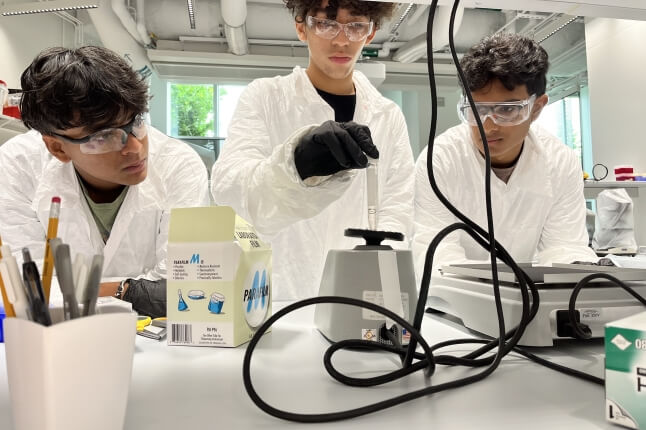

The annual “Science and Cooking for Kids” program brought former White House pastry chef Bill Yosses (photo 1) back to campus to teach students various cooking techniques and how to connect food with math and science. Liam Rushe (left, photo 2) and Anaya Benders experimented with salad dressings and emulsifiers as part of the program. (Photo courtesy of Stephanie Mitchell, Harvard Staff Photographer)

If you’ve ever tried to make your own salad dressing, then you know the challenges that dozens of local kids recently encountered at the Harvard Ed Portal in Allston.

No matter how hard they tried, or how much they shook their jars, the vinegar and oil just would not mix.

The students were gathered as part of the annual “Science and Cooking for Kids” program, coordinated by the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, and Harvard’s Public School Partnerships team, in which students learn various cooking techniques and how to connect food with math and science.

“Science and cooking are beautifully interconnected,” said Vayu Maini Rekdal, a Ph.D. student in the Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology at Harvard’s Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, and one of the session’s organizers. “Cooking was perhaps the first form of science that humans explored, and is the science that billions of people around the world unknowingly use every day.”

“Oil and vinegar cannot be friends,” said Bill Yosses, a former White House executive pastry chef, and the session’s other organizer, “unless you bring a molecule with special superpowers into the mix. Say hello to the emulsifier.” An emulsifier acts like a mediator, Yosses explained, allowing the oil and vinegar to join forces.

“I love cooking, and I love science, so I thought it would be a good idea to combine them so that we can see what cooking can teach us about science and what science can teach us about cooking,” said Yosses.

The budding scientists experimented with different ingredients to see what would work as the best — and tastiest — emulsifier. They tried mayonnaise, honey, and mustard. They added various spices and herbs. And they picked out the ingredients to make their own healthy salads to dress.

Gladys Hernandez, 11, of Brighton, said she was surprised to see honey separating from the oil and vinegar. “I totally thought they would mix together because honey is so sticky. It was interesting to see what they actually did.”

Lily Grant, 11, also of Brighton, said that making the dressing was the best part of the day. “Our dressing tasted a little sour because of all the vinegar, but we added some garlic and some honey to make it sweeter. It was delicious! Our entire salad was delicious!”

This year, in a break from past practice, the program was held in Allston at the Ed Portal and in Cambridge at the Margaret Fuller Neighborhood House.

“We thought it would be easier to bring the program out into some of the neighborhoods around Harvard, so that we could reach as many kids as possible,” said Frank Mooney, a rising senior at Stonehill College who is now in his second summer running the program with Kathryn Hollar, director of educational outreach at the Harvard Paulson School.

“Our kids love ‘Science and Cooking.’ They are engaged, excited, and learning every moment,” said Benjamin Crystal, director of school-age programs at the Margaret Fuller house. “My staff and I have learned quite a bit about teaching from watching the lessons unfold. We very much hope to continue our collaboration throughout the year and into next summer.”

The first week, the students made their own hummus. “Many naysayers were surprised at how good it tasted,” explained Mooney. “We wanted to try something easy like hummus first to show them that it’s worth trying new foods and experimenting with new tastes.”

One of the groups toured Swissbäkers in Allston, where the students learned what goes into making bread and butter: how yeast makes dough rise and how whipping cream can be turned into butter.

In other sessions, the students will make their own fruit smoothies, experimenting with different flavors and textures, and even play around with different types of chocolate. Each week, the students are sent home with various kitchen supplies so that they can try their new skills at home.

Maini Rekdal has been working to develop curricula that explore elements of science and cooking for schools and programs across the country. As a student at Carleton College in Minnesota in 2011, before coming to Harvard to work on his Ph.D., he created the Young Chefs program. Through it, he aims to use “cooking as a way to engage — as a way to get young kids interested in science.”

Yosses said when he worked at the White House, “Mrs. [Michelle] Obama would invite 30 to 40 kids and help them plant various vegetables, and then bring them back months later to see the finished product. To see them witness that, to make that connection, that we can grow our own food, take control of our own lives, harvest, wash, and cook what we put into our bodies … it was educational, it was fun, and it really became a passion of mine to help share that with young people.”

Cutting-edge science delivered direct to your inbox.

Join the Harvard SEAS mailing list.

Press Contact

Leah Burrows | 617-496-1351 | lburrows@seas.harvard.edu