Billy Koech was an electrical engineer before he even knew what one was.

As a teenager, he owned a pair of headphones with an FM receiver, but he had no way of transmitting music from his smartphone to the headphones.

Not one to leave a problem unsolved, Koech found a YouTube tutorial, taught himself to solder, and built an FM transmitter that enabled the devices to connect.

For Koech, it seemed like a perfectly natural thing to do.

“I’ve always been a tinkerer and enjoyed working with my hands,” he said. “Growing up, I remember taking a radio apart to see what was inside, then taking different pieces off and putting them back on to see what would happen to the device.”

Growing up in Kenya, Koech had the opportunity to take an electricity class at his high school, where he became fascinated by the concepts of resistance and capacitance, and the ability to design a simple circuit that could do some really incredible things.

So after being admitted to Harvard, he arrived in Cambridge ready to explore all that electrical engineering had to offer. Koech, who had never been to the U.S. before he arrived on campus, felt right at home in the tight-knit engineering community at the John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences.

“I really enjoyed building devices and programming them to achieve some goal or solve some problem. That’s what attracted me to electrical engineering,” he said. “The deeper I dove into the field, the more I found that I could hone my skills and design things that really excited me.”

While working on a personal electric vehicle with students from Harvard and the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, Koech took a break from fabrication to take the vehicle for a spin in Maxwell-Dworkin.

Looking to broaden his skill-set, the freshman jumped into a collaborative, international program SEAS co-hosted with the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology; six students from each school worked together to design and build personal electric vehicles.

Not only did Koech get the opportunity to travel to Hong Kong, he also developed a number of mechanical skills that were far outside his comfort zone, such as how to program motor controllers and how to connect components in a motor driver circuit.

“That was a big stepping stone in my college career,” he said. “From that program, I was able to develop all these mechanical engineering and 3D computational design skills that enabled me to design physical components for every course I took later.”

Honing those skills gave him the confidence to immerse himself in another extracurricular activity—Harvard Engineers Without Borders.

When Koech joined, EWB was working on two different projects—one to build a schoolhouse in Tanzania and the other to construct a water system for a community in the Dominican Republic. Koech latched on to the latter project.

“I was looking to immerse myself in other cultures to learn about some of the challenges facing other developing countries, so I chose a project that was farther from home,” he said. “I felt that by exploring regions I hadn’t been to before, I would be able to grow and learn more about working in developing countries.”

In the Dominican Republic, Koech worked as a structural engineer, designing concrete boxes that contain different valves for regulating water flow. The work was hard—he spent long hours digging up sand in the hot sun—but Koech found it to be so gratifying that he dove into another EWB project as soon as that one was finished.

Koech translates while he and Engineers Without Borders advisor Christopher Lombardo sign a partnership agreement with officials in Kibuon, Kenya.

The following year, he was promoted to a team lead for the project in Tanzania, where he and his classmates worked to build a school house and teacher’s residence in the rural community of Mkutani.

Leading a project in Africa was especially rewarding for Koech, but the next project EWB chose was even closer to home—they set out to provide a reliable source of clean drinking water for the community of Kibuon, Kenya.

“That was very exciting for me,” he said. “Going back home with all my friends from Harvard—to show them my country—was a thrill. And it felt so good to collaborate with them and my countrymen to tackle challenges that pertain to the limited availability of water.”

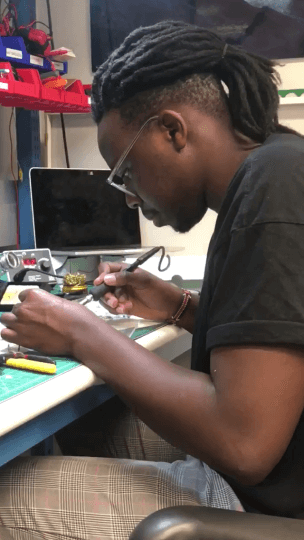

Koech is hard-at-work in the Active Learning Labs at SEAS on his senior thesis project, which involved fabricating soft magnetic and ferromagnetic materials that enable the production of soft electromagnetic actuators.

This time, Koech’s role was a little different than in year’s past. He was a co-lead of the project, and served as the primary translator for the EWB group—a role that came with a very different set of challenges than he was used to.

“I had to translate all these complex, technical terms and ideas into Swahili in the simplest way possible, and then translate the responses back to my peers in a way that presented their ideas clearly,” he said. “For EWB, it is really important that feedback from the community is incorporated into the project. It helps them take ownership of the project and ensure that it meets the needs of the community, so translation was a very important component.”

The students mapped the entire community and its infrastructure and conducted door-to-door surveys with residents to determine the best locations to drill wells, which they will design and install on a future EWB trip.

Throughout his EWB experiences, Koech learned the importance of cultural considerations in human-centered engineering projects. For instance, in Kibuon, he and his peers learned that women and children were more impacted by the lack of water, since children had to leave school early to collect water before going back home and women had to carefully manage how they allocated the water for drinking, cooking, and cleaning.

“I also learned a great deal about engineering and designing for flexibility and sustainability,” he said. “While working on projects, we would sometimes be limited by the availability of data. The challenge was ensuring that our estimations had sufficient tolerances. Sometimes we had to choose designs that could be adapted easily.”

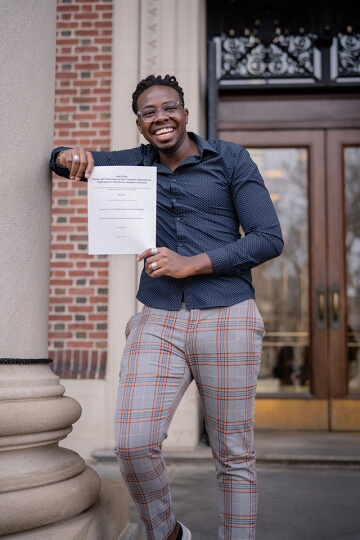

Looking to the future, Koech is planning to apply his engineering skills to a career in industry. The kid who couldn’t stop tinkering with the radio hopes to dive deeper into embedded systems, hardware, circuitry, or chips.

And although he is finishing his senior year remotely due to the COVID-19 crisis, Koech has relied on the virtual encouragement and support of the tight-knit engineering community that has made the past four years so special.

“Harvard brings together a very diverse and multi-skilled group of students, and I’ve really enjoyed collaborating with all my peers,” he said. “The community is so open and welcoming—I’ve always felt like I belong in this space.”

Press Contact

Adam Zewe | 617-496-5878 | azewe@seas.harvard.edu