News

The students in Science and Engineering for Managing COVID (ES20r) are examining the scientific and engineering basis of COVID-19 policies.

In an effort to mitigate the spread of COVID-19 on campus, Harvard placed a high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filter in the dorm room of Charlotte Moses and other residential students. The filters are designed to trap airborne particulates—like respiratory droplets that could contain the highly infectious virus.

Having a HEPA filter running might bring Moses and her peers some peace of mind, but how well do they actually work?

Thanks to Science and Engineering for Managing COVID (ES20r), Moses had the opportunity to find out. The first lab in the new Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences course challenged students to use particle generators to put their dorm room HEPA filters to the test, just days after they arrived on campus.

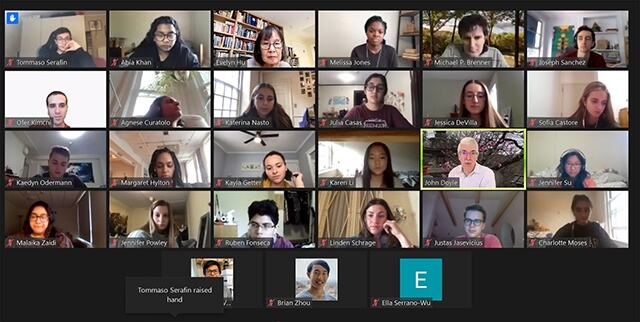

Hands-on, real-world lessons are at the crux of ES20r, which was developed by Michael P. Brenner, Michael F. Cronin Professor of Applied Mathematics and Applied Physics and Professor of Physics, John Doyle, Henry B. Silsbee Professor of Physics, and Evelyn Hu, Tarr-Coyne Professor of Applied Physics and Electrical Engineering, to examine the scientific and engineering basis of COVID-19 policies.

Moses, a first-year student, swung by a physics building for a socially-distanced pickup of lab instruments and then got right to work.

After using a sodium chloride solution and particle generator to fill the air inside her room with tiny salt particulates, Moses utilized a particle counter to see how long it took for the particles to dissipate, with and without the HEPA filter running.

“My dorm received our HEPA filters late with no instruction on how to use them, so many of my hallmates weren’t really sure if they should be turning them on and if they really would make a difference,” she said. “But our results showed that HEPA filters aren’t over-hyped. They really do work if you are concerned about disease transmission through aerosolized particles. While my hallmates were a little confused in the beginning, I’m happy to say they’ve now all turned their filters on.”

The students’ observations were summarized in a letter the instructors sent to Harvard College Dean Rakesh Khurana, outlining some suggestions to improve the communications related to HEPA filters to help ensure they are being used properly.

This Honeywell HEPA filter is in Charlotte Moses' Cabot House (Whitman Hall) dorm room. "I keep it on the 'germ' or 'turbo' setting all day and all night." she said.

That outcome comes as no surprise to instructors Hu, Brenner, and Doyle, who conceived the course as a way to educate students while generating important information University administrators can incorporate into campus COVID-19 policies and plans.

It’s uncharted territory for everyone—no one had ever conducted measurements of aerosolized particles in the dorm rooms before, Doyle said.

“What is great about the learning part of this is that they are actually able to see quantitatively some of the ideas they may have heard about, but they are also seeing how these scientific and engineering ideas really do connect with policies and guidelines,” he said. “The students show up on campus and they are able to learn more about the world around them, some aspects of the scientific process, and how it all connects to the bigger picture. Understanding what is going on around them lowers their stress levels and improves their education.”

Many of the labs that have been developed for the course are focused on issues the students face every day. For instance, later in the term they may explore cloth mask alternatives to the surgical masks that are currently being used on campus.

In addition to the hands-on lab work, the course also focuses on understanding and interpreting COVID-19 data. The cohort studied models of pandemic spread and analyzed different ways of presenting and accessing the data that forms the basis of those models.

Each student also selected a university they will monitor throughout the term, examining COVID-19 data for that school and the broader community, and analyzing how the university’s pandemic response compares to Harvard.

For Justas Jasevicius, A.B. ’21, an integrative biology concentrator taking the course remotely from his home in Lithuania, delving deeper into COVID-19 data has been both challenging and fascinating.

Jasevicius is tracking the COVID-19 response of the London School of Economics.

“No one is really tracking colleges to this extent, and there are so many things to consider,” he said. “One issue is, what if there are students off-campus who are still coming to in-person seminars? How do you account for that? It just gets exponentially more complex.”

Working around the dynamism of real-world data is a challenge for both students and instructors.

This is the way education should be. The students sensed that they were doing things they hadn’t done before. Things went wrong, they didn’t know how to make the measurements, there were no guidelines on what results they were supposed to get. But they were totally fearless. They know that what they are doing is important.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic is happening in real-time, the course is more fluid than a typical freshman seminar, with labs being tweaked at the last minute to incorporate the latest scientific information and keep up with the data the students are gathering from their experiments, said teaching fellow Agnese Curatolo, a postdoctoral fellow in applied mathematics.

It may be a bit of a whirlwind to teach, but teaching fellow Michael Cheng, A.B./S.M. ’19, now a master’s student in the MIT Technology and Policy Program, said it is rewarding to act as a mentor to first-years who are transitioning to college life during such an uncertain time.

“This class is so unique because COVID-19 is a means to an end,” he added. “Pedagogically, we are using COVID-19 as a way to introduce students to methods of scientific and engineering research. That is going to be very beneficial for them throughout their college careers.”

The course could also provide benefits to the University.

For their final projects, the students will synthesize everything they’ve learned to develop science-based advice for Harvard administrators regarding COVID-19 and plans for the spring term.

“We tell the students each week that they are on the cutting edge, and it is true. They may be freshmen, but they are on the cutting edge of the most important problem of our time,” Brenner said. “They are going to get to learn all these lessons viscerally on a problem they are all now passionate about because they are contributing to the state of the art.”

For freshman Karen Li, working on a problem that is so relevant to everyone is a driving force that motivates her as she sifts through dense datasets and tackles tough lab assignments.

At every turn, she and her peers are reminded of the critical role science must play in overcoming the COVID-19 pandemic.

“I want to learn about how communities are changing because of the pandemic and how we could have a better response next time,” she said. “I don’t think our country has had great preparation for COVID, but if we are able to understand COVID-19 better, we’ll be able to better prepare ourselves in the future.”

Cutting-edge science delivered direct to your inbox.

Join the Harvard SEAS mailing list.

Press Contact

Adam Zewe | 617-496-5878 | azewe@seas.harvard.edu