News

When Harvard University “de-densified” the campus to prevent the spread of COVID-19 last March, Robert Malate left Cambridge and traveled nearly 8,000 miles to his home on Saipan in the Northern Mariana Islands.

“That was one of the toughest things I had to do. The time zone difference was 14 hours, and all of my classes were still ongoing,” he said. “I remember waking up at 3 o’clock in the morning to go to class. Having the discipline to push through and finish that semester was a huge adjustment for me.”

Malate and several Harvard Undergraduate Aeronautics club teammates prepare to test the aircraft they designed and built. (Photo courtesy of Robert Malate)

It was also a huge accomplishment that reinforced a lesson he learned time and again over the course of his four years at Harvard: passion and perseverance really do pay off.

Valedictorian of his high school class, Malate knew he wanted to pursue engineering and that he’d have to leave the island to do it. He figured if he had to go abroad for college, why not apply to the top Ivy League school?

It was a thrill to be admitted, but also a challenge to adjust to life so far from home. The population of the entire tropical island of Saipan (only 12 miles long and 5 miles wide) is about 55,000, while metro Boston, with its cold and snowy winters, is home to nearly 5 million people.

Malate, who chose to concentrate in mechanical engineering at the John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, found that building a tight-knit network of friends was a cure for homesickness. He developed strong relationships with peers in the Harvard Undergraduate Robotics Club and Harvard Undergraduate Aeronautics, where the aerospace-minded Malate had the opportunity to build an aircraft for the first time.

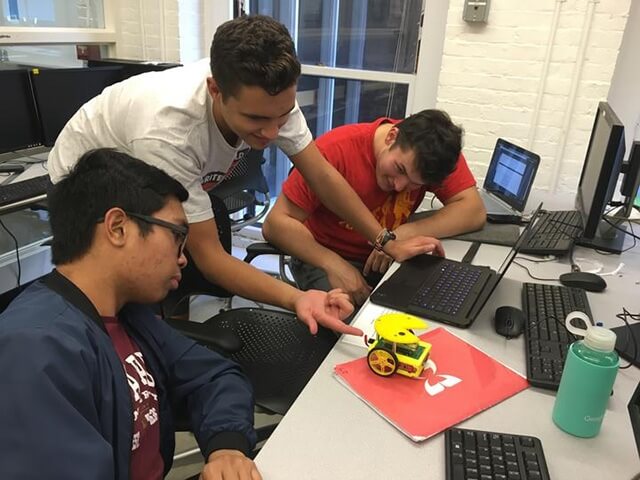

Malate and fellow members of the Harvard Undergraduate Robotics Club work on the PAC-MAN robot they built for an annual competition. (Photo courtesy of Robert Malate)

“It is cool to do all these equations and get a final derivation, but honestly it is kind of meaningless if it doesn’t translate to something,” he said. “So once I saw the aircraft actually working, I was amazed. I really enjoyed seeing how all the theoretical work translates into the real world. That taught me a whole new set of skills.”

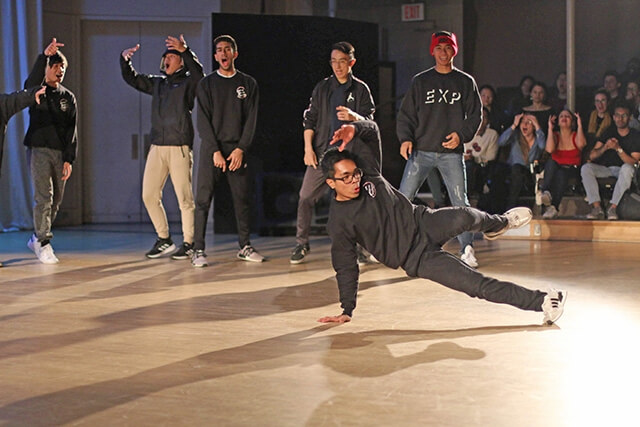

Looking for an enriching experience outside of engineering, Malate decided to join the Harvard Breakers, the University’s break dancing club. He’d never danced before, but had seen peers break dancing and was curious about what was involved.

A lot of practice, it turns out.

“It took me a year just to learn one move, but it was worth the effort,” he said. “It was very different for me. In engineering, if you have a problem, you could just work on it the night before. But when you are trying to learn something like break dancing, you have to work on it every day. Learning what it takes to master a certain move has been really rewarding for me.”

The perseverance he developed as a break dancer has come in handy throughout his academic career, especially when he decided to dive into a brand new challenge—learning Mandarin Chinese.

Malate performs with the Harvard Breakers, the University’s student break dancing organization. (Photo courtesy of Robert Malate)

To Malate, studying Chinese was much harder than even the toughest engineering problem.

“It is a really slow process for the benefits of all those language lessons to take effect,” he said. “But I really got to learn how to think a different way and communicate with people more clearly.”

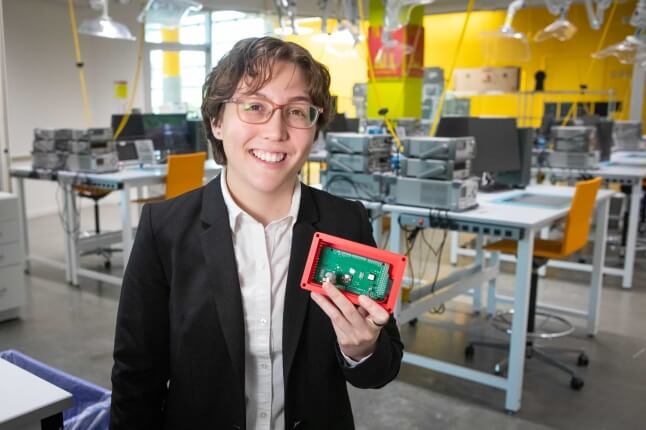

He had a chance to put those language skills to good use during a summer spent teaching at a STEM camp in Suzhou, China. During the program, Malate taught 3D printing and computer programming to middle schoolers, and though the program was taught in English, there were many times when he had to dip into his linguistic knowledge to get a point across.

“It forced me to learn the material much better. Figuring out how to explain the material to students who were 11 years old was a new challenge. I couldn’t just throw in random jargon, since English wasn’t their main language,” he said. “So I had to figure out how I could explain these concepts in ways they could understand.”

He surprised himself by how much he enjoyed teaching. It was rewarding to see others light up when they grasped concepts or shared his excitement about topics, he said. So he began serving as a teaching fellow for “Mechanical Systems” (ES 125) and “Computational Solid and Structural Mechanics” (ES 128).

The patience he honed as a teacher has been especially useful in a research environment.

Malate helps a student with an engineering problem while teaching at a STEM camp in Suzhou, China. (Photo courtesy of Robert Malate)

Fascinated by the Robobee project, Malate joined the Harvard Microrobotics Lab of Rob Wood, Charles River Professor of Engineering and Applied Sciences, during his junior year. Though he was working remotely due to the pandemic, he helped design a computer model to simulate the bending of the diminutive robot’s wings during flight.

It was a unique application of his interest in aeronautics, and helped inspire his senior thesis project. Malate is adding a buoyancy control unit to a robotic mermaid so it can dive deeper and better perform underwater tasks, like deep sea exploration.

After graduation, he plans to work internationally and focus on robotics companies that are developing tools that can improve people’s lives.

Looking back, despite the culture shock he felt at the outset of his college career, and the disruption of having to return to Saipan midway through his studies, Malate found a perfect fit at SEAS.

“Harvard engineering really is unique. Having the liberal arts environment enabled me to learn about so many other fields, and interact with people who are experts in those fields,” he said. “Harvard has so many people from vastly different backgrounds who can tell you many different stories.”

Topics: Undergraduate Student Profile

Cutting-edge science delivered direct to your inbox.

Join the Harvard SEAS mailing list.

Press Contact

Adam Zewe | 617-496-5878 | azewe@seas.harvard.edu