Manav Bansal, S.B. '22, in environmental science and engineering (Eliza Grinnell/SEAS)

Manav Bansal assumed he’d become a doctor. After all, he’s the son of two doctors, with two older sisters who’d go on to pursue careers in medicine.

A summer internship completely upended Bansal’s future plans. Following his sophomore year in high school on Long Island, Bansal became an intern at The Climate Museum in New York. Guiding visitors through the exhibit educated Bansal about the climate crisis, and he eventually joined the museum’s Youth Advisory Council, working with the New York City Department of Education and National Geographic to develop new youth-oriented climate education programs.

“It was there when I felt a passion for the subject, and I’d never felt that passion for medicine,” Bansal said. “It was clear that this was something I wanted to pursue further.”

That passion eventually led him to the environmental science and engineering concentration at the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS). Since arriving, he’s pursued his interest in climate and the environment in numerous ways: in his coursework; through research in the Mike Aziz Group, culminating in an award-winning senior capstone project on electrochemical carbon capture; and as part of a range of clubs focused on everything from clean energy to environmental activism to climate change’s particular impact on lower-resource areas of the world.

Next fall, he’ll pursue a master’s degree in energy technologies from the University of Cambridge in England as a Herschel Smith Fellow, funded by Harvard’s Herchel Smith Postgraduate Scholarship.

“We understand that one of the main reasons why we’re experiencing a rise in global temperatures and cascading effects such as more intense natural disasters and water and food scarcity is because of a rise in carbon dioxide concentration in the atmosphere,” Bansal said. “I always hope to implement technologies that are socially equitable and ensure they address communities that are the most marginalized first.”

After graduating, Manav Bansal will pursue a master’s degree in energy technologies from the University of Cambridge in England as a Herschel Smith Fellow (Eliza Grinnell/SEAS)

The SEAS environmental science and engineering program offered the ideal blend of science and technology subjects with climate education and environmental justice, so he chose it over schools with more established majors.

“I thought it was an opportunity for me to not only shape and build the program, but also learn from it,” he said. “And because it was so personalized because there weren’t a large number of students, it’d allow me to get a really hands-on education from experts in the field and make really great friendships with people who were passionate about the same things I am.”

Those friendships would be further forged through his activities in so many student clubs, many of which he joined within the first few months of being on campus. He was Co-Director of Communications for the Harvard Undergraduates for Environmental Justice, and Co-Director of Communications and Technology for the Harvard Undergraduate Clean Energy Group. Previously, he’s been part of the Harvard chapter of Engineers Without Borders, the Harvard Council of Student Sustainability Leaders, Fossil Fuel Divest Harvard, the Green Medicine Health Initiative, and the Harvard Undergraduate Think Tank, where he chaired a research project on climate change and the case for reparations. He also volunteered with the Phillips Brooks House Association, devoting his time to its Boston Refugee Youth Enrichment Extension Program.

“When I was in high school, I started to learn about the intersection of climate change, inequity and social justice,” he said. “That intersection became a key point in my narrative throughout high school. Even in college, when my studies focused more on the technical side, there was still a deliberate attempt to surround myself with all the intersections that climate has with other fields.”

Outside of the classroom and clubs, Bansal has been a member of the Aziz Group since his freshman year. Drawn to the renewable energy technology research happening there, Bansal joined the lab with a simple email to Mike Aziz, Gene and Tracy Sykes Professor of Materials and Energy Technologies.

“I’m so grateful he was thoughtful enough to accept me as a first-year student,” Bansal said. “A lot of environmental engineering courses are theoretical or based on computer modeling. Working in a lab, I learned how to work with computer code that would have a cascading effect on mechanical systems that I could physically touch. And as I was designing experiments, I’d have to learn all these new equations and formulas that I hadn’t learned in any of my classes. That forced me to look for new knowledge and really make myself an expert.”

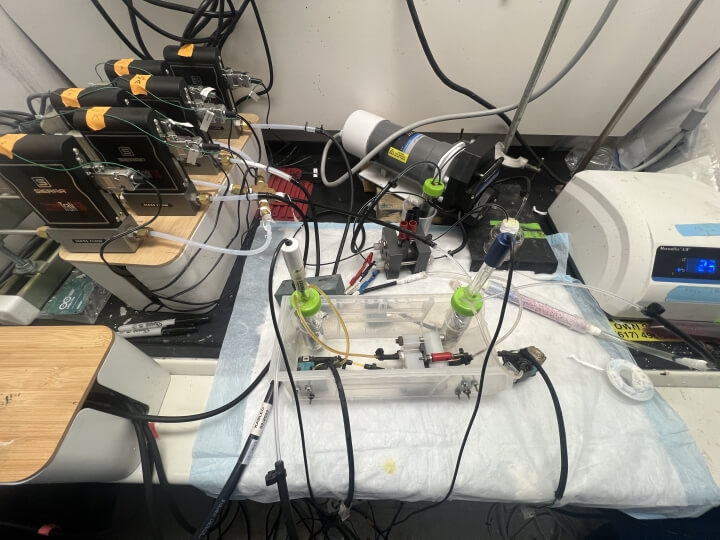

For his senior capstone project, Manav Bansal developed an electrochemical battery for capturing and then re-releasing carbon dioxide.

Aziz eventually became Bansal’s advisor for his capstone project, which recently won a Dean’s Award for Outstanding Engineering Projects. Bansal developed an electrochemical battery that could support an energy-efficient, low-maintenance system for capturing carbon dioxide (CO2) and then re-releasing it.

“There are a lot of renewable energy technologies that aim to reduce our reliance on fossil fuels, which are a main cause for these rises in CO2 concentrations, but the transition to those power sources isn’t happening as fast as we need it to in order to ensure a safe future for future generations,” he said. “Our technology is a proprietary battery system that aims to show that you can absorb CO2 from the air, and then release it. The release is crucial, because in a lot of other industries, we can use CO2 as a fuel alternative, for use in areas such as sustainable aviation or chemical feedstock. To be able to capture CO2 from the air, then use it for additional sustainable resources, provides a double-pronged approach.”

Studying abroad in London as a third-year student interested Bansal in returning to the United Kingdom for a master’s degree. The Herschel Smith program was especially appealing because it allows for up to three years of support for graduate studies. This gives Bansal time to decide if a one-year master’s degree is sufficient, or if he wants to eventually pursue a Ph.D.

“A master’s degree would be a one-year program for me to really hone in on a specific subject like energy technologies, which is an area that’s really of interest to me,” he said. “If I really want to pursue a Ph.D., Cambridge is offering this new program on sustainable materials innovation, so there’s an avenue for me to walk down if I really love the program and don’t want to end my time there.”

Bansal has tackled climate science and engineering from so many different angles in his four years at SEAS. He’s been a student, a researcher, an activist, an educator, an intern, and everything in between. But through all those different approaches and experiences one thing is clear: the relationships he’s forged are what have truly made the journey worthwhile.

“People talk all the time about how you make lifelong friends in college, but you don’t really understand the extent of that until you find your group of people,” he said. “I think being here is where I really found my group of people. Alongside the academics, I have a support system away from the classroom that makes this a new home for me. I’m able to lean on people for support, bounce back ideas or just have another person to study with. That’s really been beneficial to aiding my academic experience and enhancing it to where I can pursue what I want to to the best of my ability.”

Healing the Earth, Bansal realized, requires the multifaceted approach he has experienced at Harvard—just like treating a patient. In the end, “I always knew I would become a ‘doctor’; I just didn’t know who the patient would be.”

Press Contact

Matt Goisman | mgoisman@g.harvard.edu