News

Key Takeaways

- Harvard engineers, as part of Project CETI, have built an open-source bio-logger that adheres to sperm whales and records high-fidelity, multi-channel audio plus rich behavioral and environmental data.

- The data are tailored for machine learning analysis so that researchers can better understand whale communication.

- The technology and methods are open source and designed to be shared widely to inspire further studies in cetaceans and other species.

Say you want to listen in on a group of super-intelligent aliens whose language you don’t understand, and whose spaceship only flies by Earth once an hour. It’s not unlike what Harvard scientists and others are doing, except their target species, sperm whales, thankfully live here on Earth.

As part of the nonprofit Project CETI (Cetacean Translation Initiative), an ambitious, multi-institutional endeavor to discern the language of sperm whales, engineers in the John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS) and others have led the development of a powerful listening device that adheres to whales and records high-fidelity audio and other information that’s later analyzed by machine learning models.

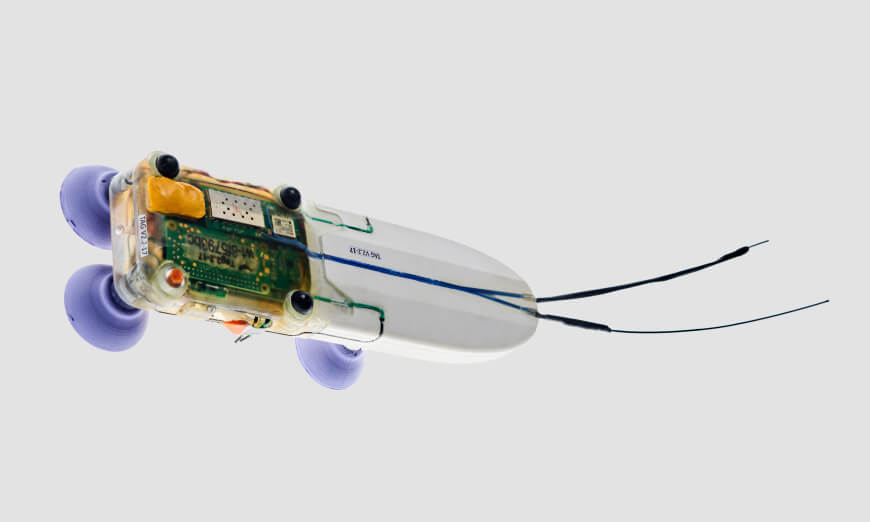

The device, called a bio-logger, collects large, high-quality datasets of whale sounds called codas, which to human ears sound like a series of rhythmic clicks, along with contextual clues like physical behavior and ocean depth. The bio-logger is among the first to be explicitly designed to capture data for interpretation by machine learning algorithms. Modern machine learning techniques can help uncover structured, non-human communication by identifying patterns and frequencies in the whale codas that humans can’t readily perceive.

Detail view of the Project CETI bio-logger. Photo credit: Spencer Lowell

The bio-logger has so far been deployed in whales off the Caribbean coast of Dominica during numerous deep-sea dives. The details of the device's design and the inspiration behind it are published in PLOS One.

“When we were looking to decode the language of whales, a key value was to have the mics placed at the best spots, for the best audio recording possible,” said Daniel Vogt, lead Harvard SEAS engineer for Project CETI and first author of the bio-logger paper. “We looked at the state of the art, what was available out there, and there was nothing that really matched what we were looking for. So we made our own.”

Lead author and Harvard engineer Daniel Vogt testing equipment in the lab. Photo credit: Spencer Lowell

Open-source technology

The Harvard-designed bio-logger and all its components and software are open-source, available to anyone in the marine biology or scientific communities. The researchers hope this structure will give rise to crowd-sourced innovation and possibly expand to other species.

“This really democratizes and opens up the field of marine science, to biologists across the world,” said David Gruber, founder and lead scientist of the five-year-old Project CETI, a National Geographic Society Program. Gruber’s work on whale communication began when he was a 2017-2018 Radcliffe Fellow.

The non-invasive bio-logger attaches to the skin of sperm whales via suction cups that were also designed by Harvard robotics researchers. It includes three synchronized, high-bandwidth hydrophones – underwater microphones – that can record sound from multiple whales talking to each other at different distances. Other features include GPS logging and transmission equipment, as well as sensors for depth, movement, orientation, temperature, and light.

Whales are tagged using a "tap and go" approach with specially adapted drones. Photo credit: Jaime Rojo

Whales can dive a mile down and stay underwater for an hour, surfacing for only a few minutes to breathe; the bio-logger is built to withstand those conditions, with battery life of about 16 hours, and audio sensitivity that picks up higher frequencies than humans can hear.

Legacy whale tagging technologies have in the past recorded many whale vocalizations and formed the basis for the field of cetacean communication. The CETI bio-logger builds on those foundational technologies but captures a richer array of data, including the ability to differentiate between different whales speaking by measuring their sounds’ origin. The datasets are helping researchers interpret the sounds and make sense of them, rather than just listening in.

A view of the CETI bio-logger's main components.

Recent results have already proven out their methods. One published study used data from bio-loggers to show that sperm whales have their own alphabet; another reports a version of vowels and diphthongs in sperm whales’ language, similar to how humans speak.

Project CETI goals

Founded in 2020, Project CETI is the world’s largest interspecies communication initiative, involving eight institutions and 50 scientists who work in artificial intelligence, natural language processing, cryptography, linguistics, marine biology, and robotics. Harvard researchers have played key scientific roles; Vogt works in the lab of Robert Wood, the Harry Lewis and Marlyn McGrath Professor of Engineering and Applied Sciences, who leads the robotics component of Project CETI and whose lab designed the clingfish-inspired suction cups that adhere the bio-logger onto the whale’s skin. Stephanie Gil, assistant professor in computer science, designed a reinforcement learning framework with autonomous drones that are used to find whales and predict when they will surface so they can be tagged. In addition, the project’s lead linguist, Gašper Beguš, received his Ph.D. at Harvard.

Adhering a microphone to a sperm whale is a 10-out-of-10 challenge across multiple fronts: Using drones to tag the animals without bothering or hurting them. Getting the tags to stick amidst a salty, wavy ocean. Retrieving the devices. Extracting and interpreting the data. The Project CETI team has reached milestones on each of these endeavors. Bringing the bio-logger to many other labs and teams should edge the project even closer to its goal of understanding how sperm whales and other cetaceans communicate, and maybe one day, answering back in their language.

“This technology could now be expanded to the millions of other species we share the planet with” Gruber said. “I see this as a massive moment, because the field of bioacoustics and artificial Intelligence can now vastly expand.”

Learn more about Project CETI: https://www.projectceti.org/

Topics: AI / Machine Learning, Bioengineering, Electrical Engineering, Materials Science & Mechanical Engineering, Research, Robotics, Technology

Cutting-edge science delivered direct to your inbox.

Join the Harvard SEAS mailing list.

Scientist Profiles

Robert J. Wood

Harry Lewis and Marlyn McGrath Professor of Engineering and Applied Sciences

Press Contact

Anne J. Manning | amanning@seas.harvard.edu