News

Key Takeaways

- Harvard engineers have developed a new 3D printing method for building soft robots that bend and change shape in predictable ways when inflated.

- The technique employs rotational multimaterial 3D printing, in which a dual-material nozzle prints filaments with a flexible outer shell and removable inner gel.

- The process could enable complex soft robots, such as flower-like actuators or hand-shaped grippers, with potential uses in surgical or other applications.

Soft robots made out of flexible, biocompatible materials are in high demand in industries from healthcare to manufacturing, but precisely designing and controlling such robots for specific purposes is a perennial challenge. What if you could 3D print a soft robot with predictable shape-morphing capabilities already built in?

Harvard 3D printing experts have shown it’s possible. A study in Advanced Materials describes a new fabrication method for printing robotic devices that feature long filaments with precisely placed hollow channels. When filled with air, the channels allow the device to bend and deform in predetermined ways.

The advance was led by graduate student Jackson Wilt and former postdoctoral researcher Natalie Larson in the lab of Jennifer Lewis, the Hansjorg Wyss Professor of Biologically Inspired Engineering in the John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS). The method combines several Harvard-developed 3D printing techniques and circumvents traditional casts and molds that are typically used to make soft robots.

“We use two materials from a single outlet, which can be rotated to program the direction the robot bends when inflated,” Wilt said. “Our goals are aligned with creating soft, bio-inspired robots for various applications.”

Rotational multimaterial 3D printing

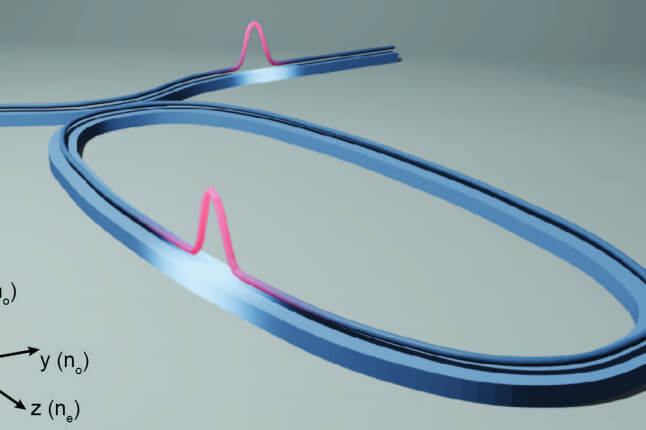

The new approach is built on an innovation of the Lewis lab called rotational multimaterial 3D printing, in which one nozzle allows more than one material to be printed simultaneously. As the machine rotates and reorients, it extrudes ink in customizable patterns. The lab has used this type of 3D printing to make soft, helical structures that act as artificial muscles and other objects.

Using this general approach, the researchers created filaments made out of a polyurethane outer shell, and an inner channel made out of a polymer commonly found in hair gels, called a poloxamer. The filaments could be arranged in lines, and in both flat and raised patterns. Through precise control of the printer nozzle’s design, rotation speed, and rate of material flow, the researchers programmed the orientation, shape and size of each inner channel.

Once the outer shell solidified, the researchers then washed away the hair gel-like inner channel. The result: tubular structures with hollow channels that can be pressurized to bend in different directions and form the basis for soft devices that expand, contract, and grasp.

Simple fabrication, complex devices

The research opens new doors toward simple fabrication of complex devices. It offers an alternative to conventional methods of making soft robots, which typically involves casting a soft material onto a mold, patterning pneumatic channels onto the surface, and encapsulating the channels onto another layer. “In this work, we don’t have a mold. We print the structures, we program them rapidly, and we’re able to quickly customize actuation,” Wilt said.

They demonstrated their new technique by spiral-printing a flower pattern in one continuous, mazelike path. They also printed a five-digit handle complete with “knuckles” that bend.

Image-based print-path planning for generating complex soft robotic matter

Their results illustrate the potential for using this type of rapid fabrication for applications ranging from surgical robotics to assistive devices for humans, according to Wilt.

Larson is now an assistant professor at Stanford University. The research had federal support from the National Science Foundation through the Harvard MRSEC (DMR-2011754) and the ARO MURI program (W911NF-22-1-0219).

Topics: Bioengineering, Materials, Materials Science & Mechanical Engineering, Research, Robotics

Cutting-edge science delivered direct to your inbox.

Join the Harvard SEAS mailing list.

Scientist Profiles

Jennifer Lewis

Hansjorg Wyss Professor of Biologically Inspired Engineering

Press Contact

Anne J. Manning | amanning@seas.harvard.edu