News

Key Takeaways

- A simple set of physical rules, including the relative thickness and faster growth of the brain’s outer cortex compared to its softer interior, explains how brains get their folds.

- Over a decade of research has produced a unified, physics-based framework for brain development that links genes to geometry, setting the stage for future studies on how folding patterns might contribute to neurological disease.

The human brain’s soft folds and ridges, arising in early development and continuing through the first 18 months of life, are a visual icon for intelligence itself.

Peeling back the layers of this fundamental biological process has been a long-sought goal of physicists and mathematicians in the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS) and the Faculty of Arts and Sciences.

Why and how does the brain fold – or misfold? Can physics shed light on the mysteries of neural development and disease?

Over a decade of probing these questions points to “yes.”

To L. Mahadevan, the Lola England de Valpine Professor of Applied Mathematics, Physics, and Organismic and Evolutionary Biology in SEAS and FAS, the brain is as much a physical object as it is an information-processing organ. A recent pair of studies in eLife brings the how and why of brain folding into sharper focus, tying the physics of folding to genetics, evolution, and diseases that arise from mis-folding.

In their new work, Mahadevan and colleagues studied the morphological diversity of brain folding across species. They also looked at how genetic mutations in human brains which were known to cause cortical malformations and mis-folding do so in a purely physical way: by changing the thickness and growth rate of the cortex, and the size of the overall brain.

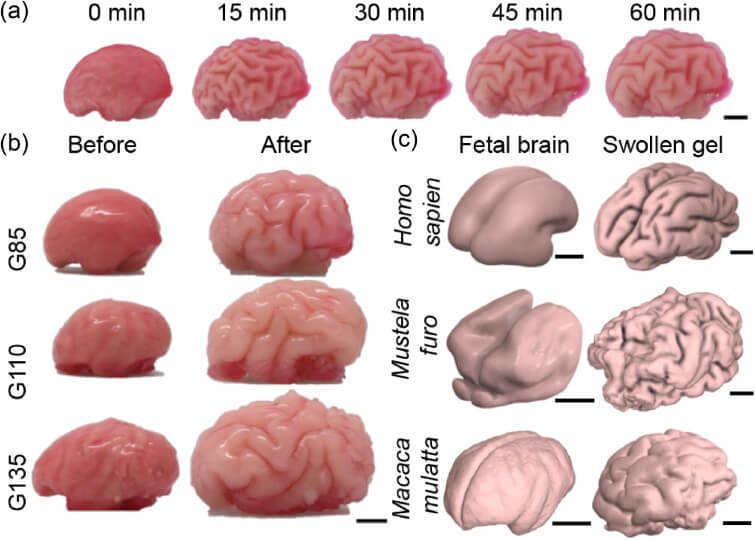

Continuous numerical simulation of the ferret brain folding.

Following brain folding in time, and across species

The researchers used ferret brains as models to validate their hypotheses. Like in humans, ferret brains start smooth and fold, and many of the genes linked to malformations in humans have counterparts that similarly affect ferrets.

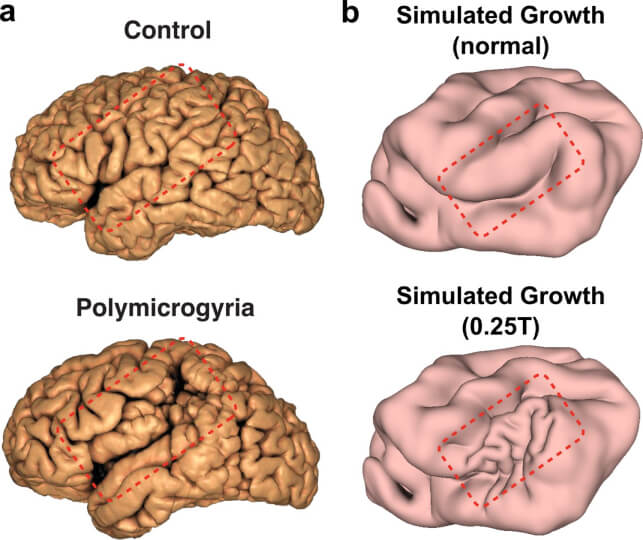

In a study published in eLife, the researchers led by first author and former Ph.D. student Gary Choi used gel models of brains and computer simulations to reproduce normal folding patterns of healthy ferret and human brains, alongside misfolding patterns seen when certain genes are disrupted. Small shifts in the physical inputs of growth led to different folding outcomes. For instance, localized thinning of the cortex generated small, tight folds that are reminiscent of polymicrogyria, a condition that can cause seizures and delayed development and is linked to the gene SCN3A.

Similarly, reducing overall growth produced smaller, less folded brains similar to microcephaly, which is associated with genes such as ASPM. In contrast, weaker folding with shallow grooves – characteristic of lissencephaly – emerged when growth was reduced and cortical thickness increased, as seen with disruptions to genes such as TMEM161B.

Together these observations and numerical and physical gel experiments bolstered the team’s hypothesis that human genetic disorders of the brain are the result of explainable physical mechanisms. The experiments bolstered the team’s hypothesis that human genetic disorders of the brain are the result of explainable physical mechanisms.

Comparison between human brain surface MRI reconstructions and ferret brain simulations for the cortical malformation polymicrogyria.

A companion paper in eLife widened the lens, with the research led by first author and former postdoctoral fellow Sifan Yin expanding to gel models and simulations of the brains of ferrets, macaque monkeys and humans. They probed further with the question, do different species have different “rules” for how their brains fold, or is the same physics at work across species?

They found that the same basic mechanism – faster growth of the outer cortical layer, relative to the softer, interior white matter – generated folding in each species. Eventual differences in folding patterns seen between ferrets, monkeys and humans weren’t due to different physical rules, but rather to different starting patterns and growth rates, the researchers found.

This convergence of physical rules across species gives Mahadevan the feeling that the biological aspects of understanding brain development are at an inflection point, the “end of a beginning.”

“Often things start out being mysterious to everyone, then become magical, when only an initiated few know how things work, and eventually become mathematical, when everyone can understand the causes,” Mahadevan said. “The most surprising thing is how simple the basic mechanism is – iterations and variations of a simple mechanical instability seem to suffice to explain much of the folding morphology.”

With the basic physics now mapped out across species, the scientists hope to dig deeper into not just how the brain folds, but exactly how those folds relate to patterns of normal and abnormal activity.

“The most important question about the brain is its function – to process information and create predictions using sensory information that it receives,” Mahadevan continued. “How do the folding patterns lead to distinctive regions of specialization associated with function e.g. visual, auditory, somatosensory information processing, while also integrating all these modalities?”

Timing is important, too. “Do these regionalizations arise simultaneously even as folding proceeds? Precede them? Succeed them?” Mahadevan asks. “To understand these requires following function as form develops, and this is a natural next question.”

Physical gel model that recapitulates the growth-driven morphogenesis mechanism across phylogeny and developmental stages.

From bread to brains

The beginnings of these research questions were planted more than a decade ago from Mahadevan and team’s unquenchable curiosity about how complex patterns emerge from simple causes. This was long before their minds were on the brain.

In his Soft Math Lab at Harvard, Mahadevan’s team has long used physical and mathematical models to explain how tissues flow and form and fold in other settings: How the body plan is laid out, how the body elongates, how organs like the gut fold into loops, how bird beaks take shape, how plant shoots straighten up. Across all these examples, the unifying theme is that simple geometrical and physical rules can and do give rise to Darwin’s “endless forms most beautiful.”

Mahadevan started thinking about brains after studying mechanical “sulcification,” or a mechanical instability that appears when soft materials are compressed – like in baking bread as it folds inward, in the palm of one’s hand, or in indented surfaces of compressed gels. In 2011, he and his student developed the first physical and mathematical framework to describe this instability in non-biological materials. They wondered: Do the same rules apply to living matter?

Breakthrough in defining simple folding principles

Mahdevan’s excitement around brain folding crystallized in a 2014 paper, with then-postdoctoral fellow Tuomas Tallinen and collaborators. There, they posed whether the diverse outcomes of brain folding could be broken down to a handful of mechanical principles.

They found that just two variables were essential to brain folding: the relative thickness of the cortex compared to the overall brain size, and the rate at which the cortex grows compared to the softer, underlying white matter.

Using models, they showed that when the outer cortical layer grows a little faster than the interior, mechanical stresses build up until the entire system buckles and folds, like skin wrinkling when squeezed. Varying cortical thicknesses and growth rates change the resulting patterns of folds. Using only these parameters, the team showed they could reproduce different brain folding patterns.

A follow-up Nature study published in 2016 tested their growth models against more realistic data: a 3D model of a smooth fetal brain based on real MRI images. They were able to mimic the differential growth between gray and white matter to cause their model brain to crease and fold, with patterns that resembled real cortical growth in humans.

“We showed that we can quantitatively explain how human fetal and neonate brains grow and fold, using a combination of theory, computation, experiment, and connections to biological observations,” Mahadevan said of that study.

Folding and misfolding

A natural next question was to understand how these experimental and computational frameworks could capture folding patterns across species, moving toward developmental and evolutionary aspects of brain folding, Mahadevan continued. “Simultaneously, we were interested in understanding how brains misfold – with obvious connections to brain dysfunction.”

Those questions led to the pair of 2025 eLife studies, which underscore the physical, seemingly universal rules that govern brain folding in humans and other mammals.

The research offers a new framework for interpreting genetic disorders that alter the shape of the brain.

“Our work sheds light on both developmental and evolutionary aspects of brain folding, and as such sets the stage for how things work normally,” Mahadevan says. “By connecting different genetic defects to how the brain misfolds, we have been able to identify a causal pathway on human brain misfolding – from genes to geometry – and how it can go awry."

Topics: Applied Mathematics, Applied Physics, Health / Medicine, Research

Cutting-edge science delivered direct to your inbox.

Join the Harvard SEAS mailing list.

Scientist Profiles

L Mahadevan

Lola England de Valpine Professor of Applied Mathematics, of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, and of Physics

Press Contact

Anne J. Manning | amanning@seas.harvard.edu