News

One of the challenges in studying diabetes and developing new treatments is that the endocrine cells that control glucose — known as islets — are hard to monitor and study. They are tiny — much smaller than cardiac cells or neurons — and densely packed together deep inside the pancreas. Islets derived from human stem cells could not only be used to study this hard-to-reach and complex system but could also be transplanted into patients to revive or replace damaged pancreatic function.

But so-called human pluripotent stem cell–derived islets tend to act immature, with less precise and dynamic responses to glucose, hindering the application of these potentially powerful models and therapeutics.

Now, in new research published in Science, a team from the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS) has developed “cyborg” pancreatic organoids with embedded electronics that record in real time how different types of stem-cell derived islets develop and communicate. The long-term monitoring revealed what makes these cells respond to glucose more accurately and how they synchronize their activity with each other as they mature.

“Our goal is to build electronics that become part of living tissue as it grows,” said Jia Liu, Assistant Professor of Bioengineering at SEAS and senior author of the paper. “For pancreatic organoids, that means we can watch how endocrine cells develop and communicate, and we can begin to test strategies — like meal-time rhythms — that help these tissues stay functionally mature.”

The research is part of a decade-long project, led by Liu, to build soft, stretchable, tissue-like electronics that integrate with living systems during development, so the device becomes part of the tissue as it grows. This so-called “cyborg tissue” has created a new way to watch, map, and ultimately control biological circuits over long periods of time. The researchers have used these embedded electronics in a range of tissues, including cardiac tissue, neural tissue and frog embryonic tissue.

Watching cells “speak” electrically — over time, in 3D

There are two major endocrine cell types in the islets: Beta cells (SC-β) respond to high glucose by releasing insulin, while alpha cells (SC-α) release glucagon when glucose drops. Like neurons, α and β cells use membrane voltage changes to trigger hormone release. As islets mature, their coupling to glucose and the threshold for hormone release increases — so tracking electrical activity is a direct way to study functional maturation.

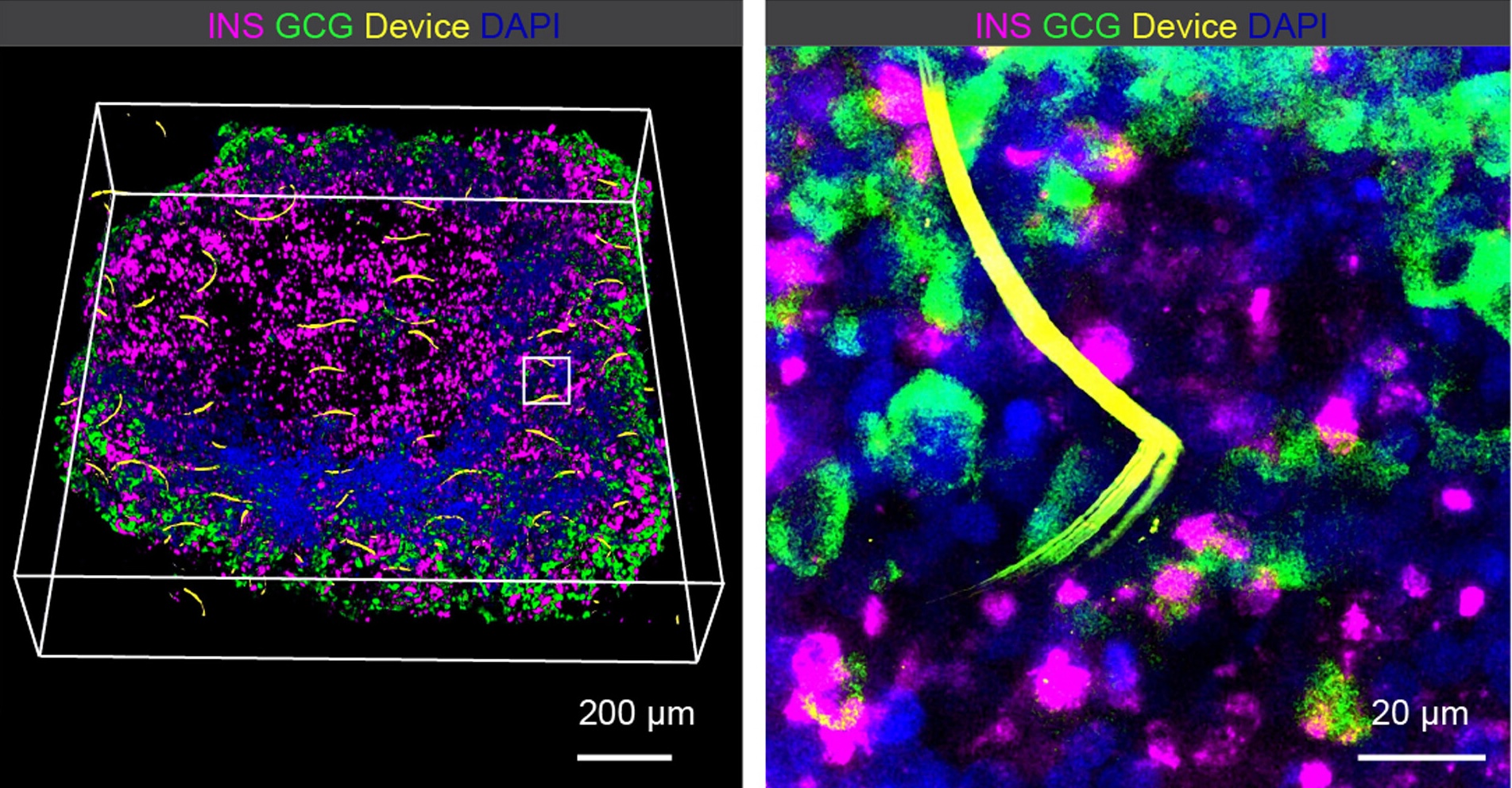

(Left) Three-dimensional rendering of fluorescence imaging of a cleared, immunostained cyborg pancreatic organoid 2 months after integration. (Right) Zoom-in view of the white box inset in the left panel shows intimate coupling of flexible interconnects from the device with SC-α and -β cells.

To capture the electrical activity of each type of cell, Liu’s team worked with Douglas Melton, Catalyst Professor, and Juan R. Alvarez- Dominguez, Assistant Professor of Cell and Developmental Biology at the University of Pennsylvania to integrate stretchable, tissue-like nanoelectronics into developing stem cell–derived pancreatic organoids, which recorded cellular activity over a series of weeks.

Because the system is incredibly noisy — with many cells firing at once — the team adopted computational tools from neuroscience that groups electrical spikes by waveform shape, helping highlight which spikes likely came from which individual cell. This so-called spike sorting allowed the team to simultaneously track single-cell electrical activity from both types of islets and distinguish their opposite responses to glucose.

With this tracking in place, the team found that SC-α and SC-β cells each have two major electrical states, depending on distinct glucose thresholds. Liu and the team found that the alpha and beta cells became more mature as they coordinated across these electrical states.

Meal-time rhythms and a first step toward active tuning

The study also connects maturation to daily eating patterns.

In typical lab culture, stem-cell derived islets can improve and then fade over time, and scientists haven’t always known why. Liu and his team found that organoids benefit from a more life-like environment by cycling glucose levels in the culture dish — essentially simulating meals.

The team also implanted stimulators to deliver electrical stimulation that enhanced glucose-stimulated activity in SC-α and SC-β cells—an early step toward actively tuning islet performance. Looking ahead, the team plans to develop closed-loop control strategies — potentially using AI — to adjust stimulation in real time.

“Taken together, this work extends a broader cyborg tissue program,”Liu said. “By turning tissue development into something we can measure continuously—and increasingly, modulate—we can start to uncover what makes human tissues truly mature, and how to keep them there for research and regenerative medicine.”

The research was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health under grant DP1DK130673.

Topics: Bioengineering, Health / Medicine, Research

Cutting-edge science delivered direct to your inbox.

Join the Harvard SEAS mailing list.

Scientist Profiles

Jia Liu

Assistant Professor of Bioengineering

Press Contact

Leah Burrows | 617-496-1351 | lburrows@seas.harvard.edu