News

Key Takeaways

- SEAS researchers have experimentally shown that a beam of light can repeatedly focus and defocus itself in free space without a lens, confirming a 1960s theoretical prediction called the Montgomery effect.

- This controllable, lensless self-imaging could enable many technologies including arrays of optical tweezers and background-free, multi-plane optical imaging.

Applied physicists in the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS) have demonstrated a new way to structure light in custom, repeatable, three-dimensional patterns, all without the use of traditional optical elements like lenses and mirrors. Their breakthrough provides experimental evidence of a peculiar natural phenomenon that had been confined mostly to theory.

Researchers from the lab of Federico Capasso, the Robert L. Wallace Professor of Applied Physics and Vinton Hayes Senior Research Fellow in Electrical Engineering, report in Optica the first experimental demonstration of the little-known Montgomery effect, in which a coherent beam of light seemingly vanishes, then sharply refocuses itself over and over, in free space, at perfectly placed distances. This lensless, repeatable patterning of light could lay the groundwork for powerful new tools in many areas including microscopy, sensing, and quantum computing.

This effect had been predicted mathematically in the 1960s but never observed under controlled lab conditions. The new work underscores not only that the effect is real, but that it can be precisely engineered and tuned.

The experiments were led by first author Murat Yessenov, a postdoctoral researcher in Capasso’s group. He and colleagues were inspired by a closely related phenomenon that is exploited in many optical technologies today.

That related phenomenon, known as the Talbot effect, happens when a narrow beam of light is sent through a device called a grating that is etched with a periodic pattern, like a picket fence. The light produces a perfect, repeated, evenly spaced image of the grating, though no lens is present. This Talbot effect is harnessed for countless technologies today that employ what’s called lensless self-imaging, including high-resolution lithography that requires perfectly spaced micro patterns; metrology and sensing applications; and optical trapping of atoms or gas particles.

But the Talbot effect has a key limitation: it only works when the starting pattern of the diffraction grating is strictly periodic. It also tends to produce unwanted copies of the pattern, as well as background light. This makes it hard to create clean, controlled, tightly focused light in free space.

In the 1960s, physicist W.D. Montgomery theorized that self-imaging should be possible for almost any pattern of light, not just periodic ones. Yet his prediction remained confined to mathematics, with only a few partial experimental demonstrations.

In the Optica study, the team used a device called a spatial light modulator, a programmable optical element similar in spirit to a digital projector, to carefully sculpt the phase of a laser beam so that it could mathematically satisfy the conditions needed for self-imaging. They created a beam that defocuses as it travels away from the starting plane, refocuses to a sharp spot at a chosen distance, and repeats this cycle multiple times in free space.

They demonstrated that the effect works not just for a single spot, but for a variety of structured beams, including donut-shaped, arrays of multiple spots, and more exotic patterns.

“Our fully programmable self-imaging platform may find application across a broad range of fields, from large-scale neutral atom-based quantum computers, to simultaneous multiplane microscopy,” Yessenov said.

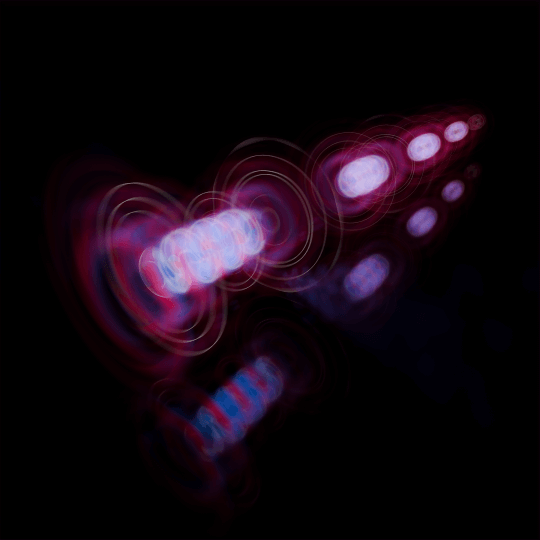

Illustration of the spatially structured self-imaging phenomenon known as the Montgomery effect. The color palette corresponds to the phase profile of the light, revealing the helical wavefront of light with orbital angular momentum, re-appearing over propagation. Image credit: Joshua Mornhinweg

The method is potentially powerful because it can concentrate light into well-defined locations while keeping background intensity low. In experimental quantum computers today that use neutral atoms as their units of computation, individual atoms are held in place at precise positions by optical tweezers. These atom arrays are typically confined to a single plane.

The Capasso lab’s new approach would make it possible to create an array of optical tweezers at several depths, potentially creating 3D architectures of quantum computers while maintaining clean, strong light trapping sites.

The approach could also be used in multi-plane optical imaging of biological samples. Existing methods require scanning down a plane of tissue and suffer from unwanted background light. The new approach by the Harvard team would allow for sharp excitation planes with minimal light in between, improving signal-to-noise ratio and reducing damage to samples.

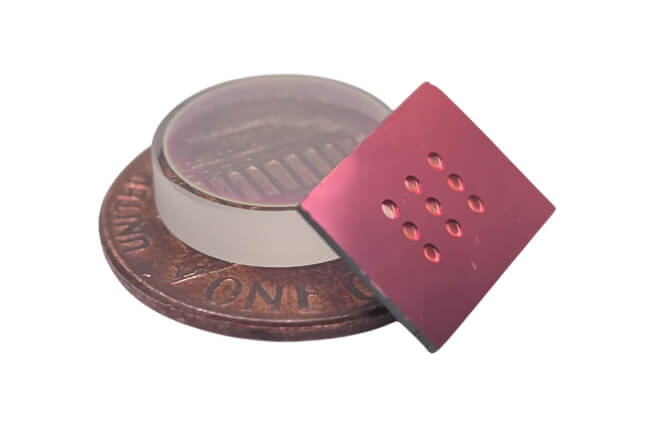

The team’s next ambition is to transfer their new, sculpted beams of light onto metasurfaces, ultra-thin nanostuctured optical elements that can maintain exquisite control of light and can be fabricated like microchips.

The paper was co-authored by Luca Sacchi, Alfonso Palmieri, Layton A. Hall, and Ayman F. Abouraddy. It was supported federally by the Office of Naval Research (N00014-20-1-2450, N00014-17-1-2458, N00014-20-1-2789); the Air Force Office of Scientific Research (FA9550-22-1-0243); and Los Alamos National Laboratory (20251140PRD1).

Topics: Applied Physics, Metasurfaces, Optics / Photonics, Research, Technology

Cutting-edge science delivered direct to your inbox.

Join the Harvard SEAS mailing list.

Scientist Profiles

Federico Capasso

Robert L. Wallace Professor of Applied Physics and Vinton Hayes Senior Research Fellow in Electrical Engineering

Press Contact

Anne J. Manning | amanning@seas.harvard.edu