News

Key Takeaways

- SEAS researchers have developed OpenMetabolics, an open-source, smartphone-based activity monitor that uses machine learning and leg motion to estimate calories burned.

- Lab studies show OpenMetabolics outperforms state-of-the-art smartwatches and fitness trackers.

Though it might feel great to finish a workout and see “calories burned” pop up on your smartwatch, that number is often surprisingly inaccurate, with estimated error rates of 30-80%. The watch’s software makes its best guess based on variable factors like heart rate, wrist motion, height and weight, without actually measuring expended energy.

Harvard biomechanics researchers have a better way. A new study from the lab of Patrick Slade, assistant professor of bioengineering in the John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS), introduces an open-source, smartphone-based activity monitor called OpenMetabolics that employs machine learning to interpret a person’s leg muscle activity into calories burned. A lab study with human participants found that the Harvard device has double the accuracy of commercial smartwatches and activity trackers. The research could not only provide more accurate measures of exercise, but it could also help scientists create higher-quality studies of health outcomes from physical activity.

Researchers recruited study participants to validate the OpenMetabolics model against other, common fitness-tracking systems.

“Physical activity is critical for management of many aspects of health,” said Slade. “By relying on a smartphone-based system, this approach can be easily deployed for large-scale use and research studies, even in underserved areas.”

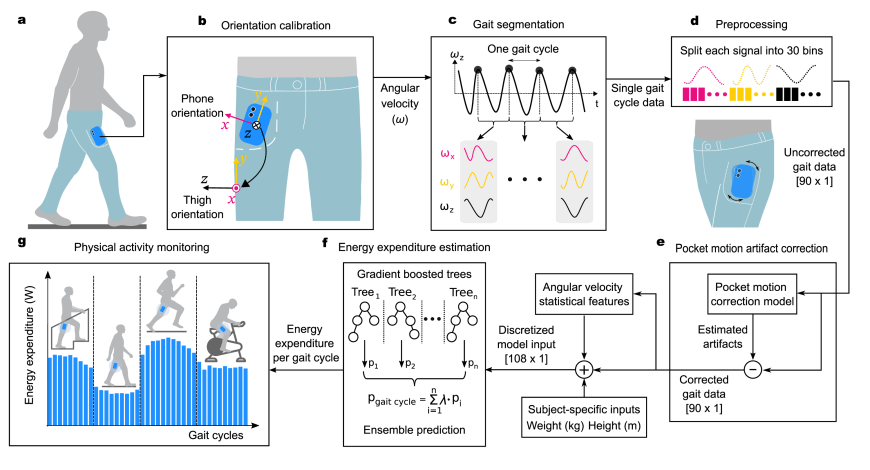

Published in Communications Engineering, the study was led by Ph.D. student Haedo Cho, who re-developed a machine learning model that Slade’s group had previously shown could accurately extract energy expenditure values from leg motion. The model uses continuous motion data captured by the smartphone’s gyroscope and accelerometer and interprets those swings and movements as values for expended energy.

Previous iterations of the lab’s activity monitor required a heavily customized system attached to a person’s leg in two places. Cho aimed to redeploy OpenMetabolics via smartphone sensors only, across varying types of people, movements, and activities. His work brings the technology closer to a widely deployable, commercial or high-quality research device.

Cho and colleagues recruited 30 participants of varying ages, sizes, and fitness levels to validate the lab’s smartphone-based model against other, more common systems, such as those found in fitness trackers like the Fitbit heart-rate model or pedometer. Participants wore the devices while performing activities like walking, biking and stair-climbing.

Cho designed the experiments to capture real-life activities. “Many biomechanics studies that evaluate physical activity are performed in the lab on a treadmill … but this does not capture how people walk in everyday life,” Cho said. “People vary their speed during the day. When I catch a bus, I might walk fast. If I’m grocery shopping at Trader Joe’s, I might walk slowly. We emulated these types of scenarios through audio prompts.”

Cho also created “a pocket motion artifact correction model,” which preserves the accuracy of the energy data despite the smartphone bouncing around in people’s pockets, in different styles of clothing, at different angles.

A pocket motion artifact correction model preserves accuracy of energy data despite movement of the smartphone.

Cho said he was particularly motivated to work on better methods for measuring physical activity due to large gaps in population-level data in many parts of the world, where smartwatches and other measures are not common, but where smartphones are prevalent.

What’s more, as a marathon runner he’s personally seen calorie information that felt wildly incorrect. “I think we should do a better job on this, because between what people perceive, and what the devices tell them, there is probably some mismatch,” Cho said.

Slade added that the team is actively exploring the use of their technology to tackle global health challenges, supported by a Harvard Impact Labs Fellowship. Slade’s fellowship work is focused on understanding and addressing cardiovascular health risks for countries in Latin America.

The research was also supported by the Harvard Dean’s Competitive Fund for Promising Scholarship and the Raj Bhattacharyya and Samantha Heller Assistive Technology Initiative Fund.

Topics: AI / Machine Learning, Applied Mathematics, Bioengineering, Electrical Engineering, Research, Robotics, Technology, Wearable Devices

Cutting-edge science delivered direct to your inbox.

Join the Harvard SEAS mailing list.

Scientist Profiles

Patrick Slade

Assistant Professor of Bioengineering

Press Contact

Anne J. Manning | amanning@seas.harvard.edu