News

Cheetahs stalk around a meters-high termite mound in Namibia (Image courtesy of WikiCommons)

Termite construction projects have no architects, engineers or foremen, and yet these centimeter-sized insects build complex, long-standing, meter-sized structures all over the world. How they do it has long puzzled scientists.

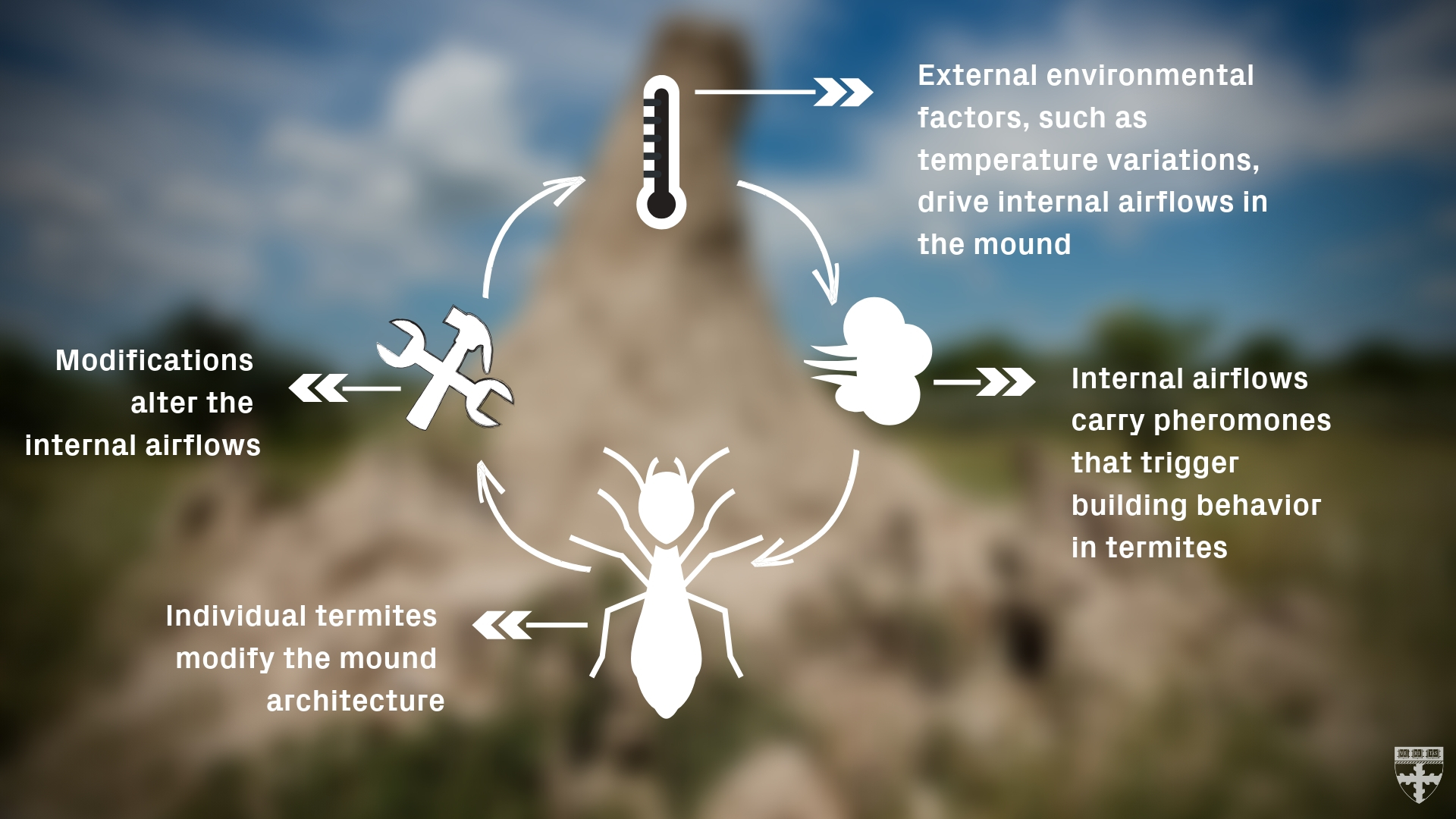

Now, researchers from the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences and the Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology have developed a simple model that shows how external environmental factors, such as daytime temperature variations, cause internal flows in the mound which move pheromone-like cues around, triggering building behavior in individual termites. Those modifications change the internal environment, triggering new behaviors and the cycle continues.

The model explains how differences in the environment lead to the distinct morphologies of termite mounds in Asia, Australia, Africa, and South America.

This new framework demonstrates how simple rules linking environmental physics and animal behavior can give rise to complex structures in nature. It sheds light on broader questions of swarm intelligence and may serve as inspiration for designing more sustainable human architecture.

The research is published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“Our theoretical framework shows how living systems can create micro-environments that harness matter and flow into complex architectures using simple rules, by focusing on perhaps the best-known example of animal architecture — termite mounds,” said L. Mahadevan said L. Mahadevan, the Lola England de Valpine Professor of Applied Mathematics, of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, and of Physics and senior author of the study. “As Winston Churchill once said ‘We shape our buildings and thereafter they shape us.’ We can quantify this statement by showing how complex structures arise by coupling environmental physics to simple collective behaviors on scales much larger than an organism.”

While they might look like apartment complexes, termite mounds actually function as a ventilation system for the colony that lives deep underground. In previous research, Mahadevan and his team found that changes in external temperatures throughout the day drive changes in airflow, temperature, and humidity inside the termite mound.

These changes in airflow carry information-containing odors to termites inside the mound. These information clouds — made up of pheromones and metabolic gases such as carbon dioxide — tell termites where to adjust the mound. If, for instance, one section of the mound is too warm, that temperature change will trigger a change in air flow, which will carry construction-cues to nearby workers. The termites will follow their senses to that section and adjust the mound to reduce temperature. That change in temperature will change the air flow and the termites will change their behavior.

By quantifying this feedback loop, the model developed by the Mahadevan group presents a minimal description that captures the essential features of mound morphogenesis and generates a wide range of typical mound morphologies.

“The wide array of termite mound shapes and sizes predicted by our model reflects the diverse range of mound morphologies observed in nature,” said Alexander Heyde, a Harvard Ph.D. student and co-first author of the study. “Some mounds are tall and narrow, while others are small and compact. Depending on the physical and behavioral parameters at play, the mounds of different termite species can look remarkably different.”

“Our model presents a simple answer to a long-standing question in termite ecology, a field which already inspires and informs the interdisciplinary communities of bio-inspired engineering and swarm intelligence. This research challenges us to learn how to build sustainable architectures that harness, rather than fight, the natural variations in our environment,” said Mahadevan.

The research was co-authored by Samuel Ocko, former graduate student in the group and now a postdoctoral fellow at Stanford. It was supported in part by the National Science Foundation and the MacArthur Foundation.

Topics: Applied Mathematics, Environment

Cutting-edge science delivered direct to your inbox.

Join the Harvard SEAS mailing list.

Press Contact

Leah Burrows | 617-496-1351 | lburrows@seas.harvard.edu