News

Key Takeaways

- Harvard SEAS researchers have developed a mathematical framework for optimizing the design of rolling contact joints, which are made of rolling surfaces and flexible connectors.

- To demonstrate their method, they developed a knee-like joint that reduced misalignment by 99% compared with standard mechanisms, and a robotic gripper that could hold three times the weight of a conventionally designed gripper.

Consider the marvelous physics of the human knee. The largest hinge joint in the body, it has two rounded bones held together by ligaments that not only swing like a door, but also roll and glide over each other, allowing the knee to flex, extend, and balance.

Researchers in the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS) have devised a new way to design knee-like joints in robots, called rolling contact joints, that could lead to better robotic grippers, more tailored assistive devices for humans, and robots that move as gracefully as animals.

Published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the new design approach optimizes how rolling contact joints are designed on a computer. It does so by simultaneously adjusting the shape of each of the joint’s key components to match a desired force or application, such as the end of a robotic gripper, or the appendage of a human-like robot.

“Whenever you have some robot, and you have an idea of what it needs to do – maybe it’s a walking robot – you can start to think about the best places to output force,” said Colter Decker, a Ph.D. student at SEAS and first author of the study. “For something that’s walking, you might want more force near the end of the stride to push off with, for example. If we can embed those decisions into the mechanics of the robot itself, then we can create robots that are more efficient. They can use smaller actuators because the energy is targeted specifically where it needs to be.”

“We try to think about robot design as being closely coupled with task and control,” said Robert J. Wood, the Harry Lewis and Marlyn McGrath Professor of Engineering and Applied Sciences and senior author of the paper. “We aim to offload as much motion control as possible to the mechanics and materials of the robot, so that the control system can focus on task-level goals. Colter’s methods do exactly that, and in a very elegant way, both mathematically and mechanically.”

Inspiration from gripper project

The idea for developing a better way to design joints was inspired by another project in Wood’s lab: How to make a soft robotic gripper that could gently wrap around objects but also apply strong forces.

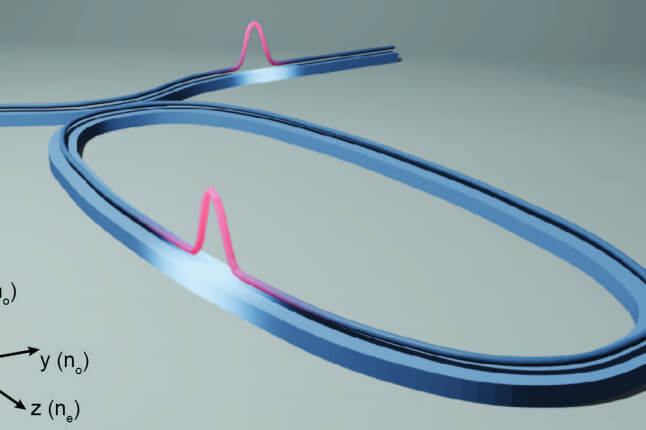

Looking for ways to combine rigid links with soft, flexible joints — much like the bones and cartilage of a human hand — led them to take a close look at rolling contact joints, which are pairs of curved surfaces that roll against each other and are held together with flexible connectors.

An optimized rolling contact joint.

In robotics, deciding how a joint should move is usually handled by software and control algorithms. In this new approach, those choices inform the geometric design of each joint.

While bearings and four-bar linkages are more widely used as joints in existing robots, rolling contact joints offer unique advantages such as flexibility, low friction, and high wear resistance that make them favorable options in specific applications, Decker continued.

Prototype knee joint, gripper

To demonstrate their new design method, the team built two prototypes: A knee-like joint, and a two-finger robotic gripper.

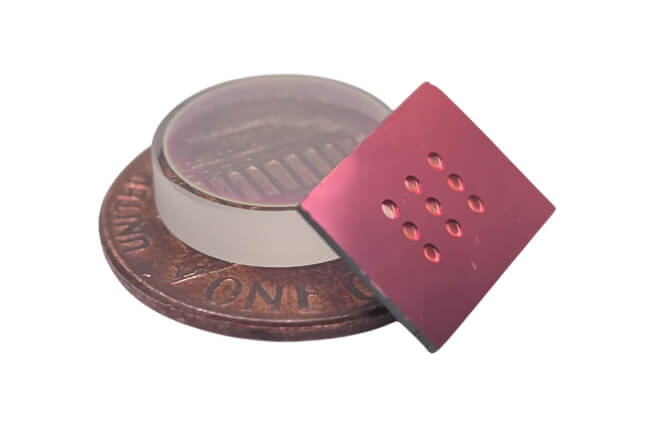

A robotic gripper made with optimized rolling contact joints.

Knee-assist devices and exoskeletons often use simple bearings placed near the knee, which can create painful misalignment because a real knee hinges but also shifts, rolls, and slides. Mapping the average path of a human knee, the researchers used their new method to make an optimized rolling contact joint that closely follows real knee motion. They compared their custom-designed joint to a standard one.

Their optimized joint performed spectacularly, correcting misalignment by 99% when compared against standard devices. The results point to a future where things like knee braces, exoskeletons, or even joint replacements could be tailored to an individual’s exact joint motion.

With their prototype robotic gripper, they optimized the joints so that the fingers would deliver maximum force depending on the size of the object. Their gripper was able to hold more than three times as much weight as a version built from standard circular joints and pulleys for the same actuator input.

While traditional rolling contact joints are built from circular surfaces, the Harvard team’s new mathematical method allows for noncircular and irregular shapes that follow unusual paths.

“We did a bunch of math to say, if you have some specific desired trajectory that you want the joint to follow, and you have some specific force transmission ratio along that trajectory, can we find surfaces and pulleys that will exhibit those properties?” Decker said. “Then we can apply that design process to optimize joints for tasks like walking, jumping, or grabbing.”

Being able to optimize human-like joints for different applications opens many avenues of exploration, from task-specific robots, to assistive robotics, to studying the biomechanics of animals, Decker said. “Now that we can design the joints, we can start applying them to all of these different scenarios,” he said.

The paper was co-authored by Tony G. Chen and Michelle C. Yuen. It received federal support from a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship under Grant No. DGE 2140743.

Topics: Applied Physics, Bioengineering, Electrical Engineering, Industry, Materials Science & Mechanical Engineering, Research, Robotics, Technology

Cutting-edge science delivered direct to your inbox.

Join the Harvard SEAS mailing list.

Scientist Profiles

Robert J. Wood

Harry Lewis and Marlyn McGrath Professor of Engineering and Applied Sciences

Press Contact

Anne J. Manning | amanning@seas.harvard.edu