News

The human kidney filters about a cup of blood every minute, removing waste, excess fluid and toxins from it, while also regulating blood pressure, balancing important electrolytes, activating Vitamin D, and helping the body produce red blood cells.

This broad range of functions is achieved in part via the kidney’s complex organization. In its outer region, more than a million of microscopic units, known as nephrons, filter blood; reabsorb necessary nutrients; and secrete waste in the form of urine.

To direct urine produced by this enormous number of blood-filtering units to a single ureter, the kidney establishes a highly branched three-dimentional, tree-like system of “collecting ducts” during its development. In addition to directing urine flow to the ureter and ultimately out of the kidney, collecting ducts reabsorb water which the body needs to retain, and maintains the body’s balance of salts and acidity at healthy levels.

Finding ways to recreate this system of collecting ducts is the focus of researchers and bioengineers who are interested in understanding how duct defects cause certain kidney diseases, underdeveloped kidneys, or even the complete absence of a kidney. Being able to fabricate the kidney’s plumbing system from the bottom up would be a giant step toward tissue replacement therapies for many patients waiting for a kidney donation: Alone in the U.S., 90,000 patients are on the kidney transplant waiting list. However, rebuilding this highly branched fluid-transporting ductal system is a formidable challenge and not possible yet.

Now, a team of bioengineers at the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS) and the Wyss Institute at Harvard University have developed a platform that combines kidney-specific stem cell differentiation and organoid culture technology with bioengineering approaches to address this challenge. The team is led by Jennifer Lewis, the Hansjörg Wyss Professor of Biologically Inspired Engineering at SEAS.

After creating an extracellular matrix that can be 3D bioprinted and supports the differentiation of human induced pluripotent stem cells into complex collecting duct organoids, the researchers engineered renal collecting ducts at two different scales to mimic the tubular collecting duct network and the drainage outlet. Upon bioprinting extensive tubular networks adjacent to larger, perfusable tubular duct structures, the two types of orthogonally-fabricated structures formed interconnections, demonstrating a practical way to build an integrated, tissue-scale collecting duct network. The findings are published in Cell Biomaterials.

“Our newly advanced platform enables us to create perfusable collecting duct tubules for multiple applications, including drug discovery and disease modeling, and ultimately, biofabrication of whole organs for therapeutic use with integrated nephron units and collecting duct networks,” said Lewis, who leads the Wyss Institute’s 3D Organ Engineering Initiative.

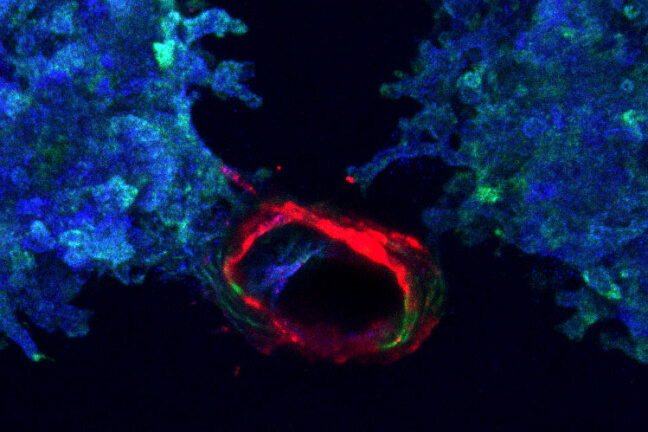

Printed ureteric tubule networks embedded in matrix, marked with green, connecting to a central, open ureteric bud-lined channel, marked with red.

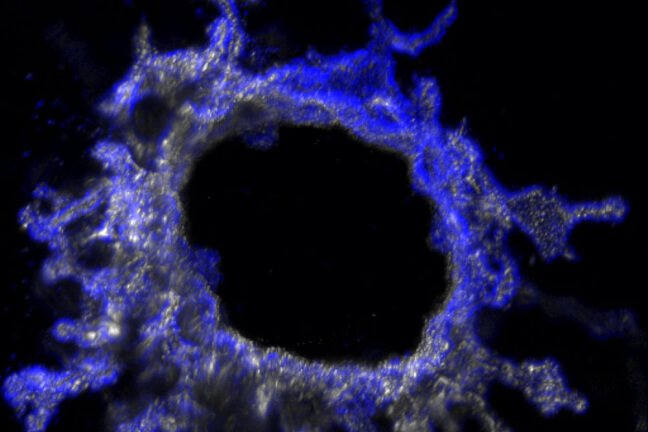

This immunofluorescence image shows a cross-section of a ureteric bud tubule-on-chip with a central perfusable channel, and cells budding into smaller tubules within the surrounding matrix.

Reverse engineered kidney development

During normal kidney development, the so-called “ureteric bud” functions as a seed for the entire collecting duct network. As a tiny tube that grows and splits, it creates all urine-collecting channels while also instructing other cells in the kidney’s cortex to differentiate into the blood-filtering nephrons. Emulating this tubular organization poses a particular challenge to bioengineers who aim at recreating the kidney’s duct network in the lab.

To replicate renal development, methods have been developed that allow researchers to differentiate human pluripotent stem cells into kidney “organoids,” aggregates of cells that exhibit many organizational features of the kidney, including nephrons and collecting duct-like tubular structures. However, organoids don’t have an inlet and outlet and their collecting ducts are poorly formed and remain relatively unorganized, thus falling short of a functional system.

“To create a new inroad into this problem, we essentially cracked open kidney organoids and leveraged their potential to develop tubular structures. By using organoid biology in combination with different tissue engineering approaches, we succeeded in building renal tubular networks lined by collecting duct cells that connect with a central outlet,” said co-first author Kayla Wolf, who with the study’s other first author Ronald van Gaal, spearheaded the project in Lewis’ group as a postdoctoral fellow.

As a prerequisite for fabricating longer and more complex tubular networks from the bottom up, the team first developed and optimized a matrix made of collagen and tiny fragments of natural basement membrane components. In normal human tissues, cells produce matrix to hold tissue together and maintain its function. In the engineering of collecting duct tissues, the extracellular matrix enabled the bioprinting process and supported the growth and differentiation of cells placed into it.

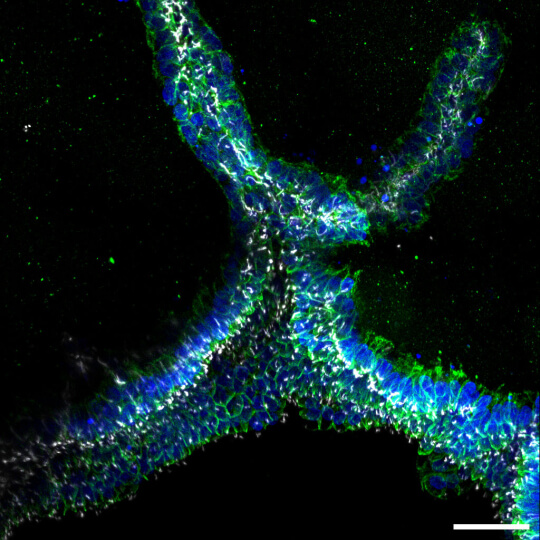

Engineered ureteric bud tubules bud from the central channel and branch into the surrounding matrix.

As a next step, Lewis’ team will test whether the engineered collecting duct network can integrate with nephron-rich features. In the meantime, these duct models are of interest for understanding diseases, such as polycystic kidney disease, that primarily originate in the collecting ducts.

Other authors on the study are Sebastien Uzel, Jonathan Rubins, Aline Klaus, Amelie Printz, Pooja Nair, Katharina Kroll, Paul Stankey, and Lisa Satlin. The study was funded by the Wellcome LEAP Human Organ Physiological Engineering (HOPE) program, NIH Re(Building) a Kidney Consortium (under award NIH UC2DK126023), an NIH F32 Ruth L. Kirschstein national postdoctoral research award to Kayla Wolf, and a Rubicon grant from the Dutch Research Council to Ronald van Gaal.

Topics: Bioengineering, Health / Medicine, Materials Science & Mechanical Engineering, Research

Cutting-edge science delivered direct to your inbox.

Join the Harvard SEAS mailing list.

Scientist Profiles

Jennifer Lewis

Hansjorg Wyss Professor of Biologically Inspired Engineering

Press Contact

Anne J. Manning | amanning@seas.harvard.edu